Cognitive effects: Difference between revisions

>Josikins No edit summary |

>Oskykins m Text replace - "Delineation of thought" to "Thought delineation" |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{{Main|Information processing suppression}} | {{Main|Information processing suppression}} | ||

{{:Information processing suppression}} | {{:Information processing suppression}} | ||

=== | ===Thought delineation=== | ||

{{Main| | {{Main|Thought delineation}} | ||

{{: | {{:Thought delineation}} | ||

===Language suppression=== | ===Language suppression=== | ||

{{Main|Language suppression}} | {{Main|Language suppression}} | ||

Revision as of 05:46, 13 May 2015

This article attempts to break down the potential cognitive effects contained within all psychoactive substance induced experiences into simple, easy to understand titles, descriptions and levelling systems. This will be done without depending on metaphors, analogies or personal trip reports. The article starts off with descriptions of the simpler effects and works its way up towards more complex experiences as it progresses. For more subjective effect components see our complete index.

Suppressions

Thought deceleration

Thought deceleration (also known as bradyphrenia)[1] is defined as the process of thought being slowed down significantly in comparison to that of normal sobriety. When experiencing this effect, it will feel as if the time it takes to think a thought and the amount of time which occurs between each thought has been slowed down to the point of greatly impairing cognitive processes. It can manifest itself in delayed recognition, slower reaction times, and fine motor skills deficits.

Thought deceleration is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis suppression and sedation in a manner which not only decreases the person's speed of thought, but also significantly decreases the sharpness of a person's mental clarity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of depressant compounds, such as GABAergics,[2][3][4] antipsychotics,[5] and opioids.[6][7][8] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogens such as psychedelics,[9] dissociatives,[10] deliriants,[4][11] and cannabinoids.[12][13][14][15]

Emotion suppression

Emotion suppression (also known as flat affect, apathy, or emotional blunting) is medically recognized as a flattening or decrease in the intensity of one's current emotional state below normal levels.[16][17][18] This dulls or suppresses the genuine emotions that a person was already feeling prior to ingesting the drug. For example, an individual who is currently feeling somewhat anxious or emotionally unstable may begin to feel very apathetic, neutral, uncaring, and emotionally blank. This also impacts the degree to which the person will express their emotional state through body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions.

It is worth noting that although a reduction in the intensity of one's emotions may be beneficial at times (e.g., the blunting of an anger response in a volatile patient), it may be detrimental at other times (e.g., emotional indifference at the funeral of a close family member).[19]

Emotion suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as motivation suppression, thought deceleration, and analysis suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of antipsychotic compounds, such as quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone.[16][20] However, it can also occur in less consistent form under the influence of heavy dosages of dissociatives,[21][22] SSRI's,[19][23] and GABAergic depressants[24].

Information processing suppression

Analysis depression is defined as a distinct decrease in a person's overall ability to process information[25][26][27] and logically or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios.[28] The experience of this effect leads to significant difficulty contemplating or understanding basic ideas in a manner which can temporarily prevent normal cognitive functioning.

Analysis suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as sedation, thought deceleration, and emotion suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of antipsychotic compounds,[25][26][28] and is associated with long term use of such drugs[29] like quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone. However, it can also occur in a less consistent form under the influence of heavy dosages of dissociatives, cannabinoids,[27] and GABAergic depressants[30].

Thought delineation

Thought disorganization is defined as a state in which one's ability to analyze and categorize conceptual information using a systematic and logical thought process is considerably decreased. It seemingly occurs through an increase in thoughts which are unrelated or irrelevant to the topic at hand, thus decreasing one's capacity for a structured and cohesive thought stream. This effect also seems to allow the user to hold a significantly lower amount of relevant information in their train of thought which can be useful for extended mental calculations, articulating ideas, and analyzing logical arguments.

Thought disorganization is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis depression and thought acceleration. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic and depressant compounds, such as dissociatives,[31][32][33][34] psychedelics,[31][35] cannabinoids,[31][36][37] and GABAergics.[38][39] However, it is worth noting that the same stimulant or nootropics compounds which induce thought organization at lower dosages, can also often result in the opposite effect of thought disorganization at their higher dosages.[31][39][40][41]

Language suppression

Language depression (also known as aphasia) is medically recognized as the decreased ability to use and understand speech.[42] This creates the feeling of finding it difficult or even impossible to vocalize one's own thoughts and to process the speech of others. However, the ability to speak and to process the speech of others doesn't necessarily become suppressed simultaneously; a person may find themselves unable to formulate a coherent sentence while still being able to perfectly understand the speech of others.

Generally, this effect can be divided into four broad categories:[42]

- Expressive (also called Broca's aphasia): difficulty in conveying thoughts through speech or writing. The person knows what she/he wants to say, but cannot find the words he needs. For example, a person with Broca's aphasia may say, "Walk dog," meaning, "I will take the dog for a walk," or "book book two table," for "There are two books on the table."

- Receptive (Wernicke's aphasia): difficulty understanding spoken or written language. The individual hears the voice or sees the print but cannot make sense of the words. These people may speak in long, complete sentences that have no meaning, adding unnecessary words and even creating made-up words. For example, "You know that smoodle pinkered and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before." As a result, it is often difficult to follow what the person is trying to say and the speakers are often unaware of their spoken mistakes.

- Global: People lose almost all language function, both comprehension and expression. They cannot speak or understand speech, nor can they read or write. This results from severe and extensive damage to the language areas of the brain. They may be unable to say even a few words or may repeat the same words or phrases over and over again.

- Anomic (or amnesiac): the least severe form of aphasia; people have difficulty in using the correct names for particular objects, people, places, or events.

Language suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis depression and thought disorganization. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of antipsychotic compounds, such as quetiapine,[43] haloperidol,[44] and risperidone.[45] However, it can also occur in a less consistent form under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics,[46] dissociatives,[46][47] and deliriants.[48] This is far more likely to occur when the person is inexperienced with that particular hallucinogen.

Amnesia

Amnesia is defined as a global impairment in the ability to acquire new memories regardless of sensory modality, and a loss of some memories, especially recent ones, from the period before amnesia began.[49] During states of amnesia a person will usually retain functional perceptual abilities and short-term memory which can still be used to recall events that recently occurred; this effect is distinct from the memory impairment produced by sedation.[50] As such, a person experiencing amnesia may not obviously appear to be doing so, as they can often carry on normal conversations and perform complex tasks.

This state of mind is commonly referred to as a "blackout", an experience that can be divided into 2 formal categories: "fragmentary" blackouts and "en bloc" blackouts.[51] Fragmentary blackouts, sometimes known as "brownouts", are characterized by having the ability to recall specific events from an intoxicated period but remaining unaware that certain memories are missing until reminded of the existence of those gaps in memory. Studies suggest that fragmentary blackouts are far more common than "en bloc" blackouts.[52] In comparison, En bloc blackouts are characterized by a complete inability to later recall any memories from an intoxicated period, even when prompted. It is usually difficult to determine the point at which this type of blackout has ended as sleep typically occurs before this happens.[53]

Amnesia is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as disinhibition, sedation, and memory suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of GABAergic depressants, such as alcohol,[54] benzodiazepines,[55] GHB,[56] and zolpidem[57]. However, it can also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, Salvia divinorum, and deliriants.

Personal bias suppression

Personal bias suppression (also called cultural filter suppression) is defined as a decrease in the personal or cultural biases, preferences, and associations which a person knowingly or unknowingly filters and interprets their perception of the world through.[58]

Analyzing one's beliefs, preferences, or associations while experiencing personal bias suppression can lead to new perspectives that one could not reach while sober. The suppression of this innate tendency often induces the realization that certain aspects of a person's personality, world view and culture are not reflective of objective truths about reality, but are in fact subjective or even delusional opinions.[58] This realization often leads to or accompanies deep states of insight and critical introspection which can create significant alterations in a person's perspective that last anywhere from days, weeks, months, or even years after the experience itself.

Personal bias suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as conceptual thinking, analysis enhancement, and especially memory suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogens such as dissociatives and psychedelics. However, it can also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of very heavy dosages entactogens and cannabinoids.

Memory suppression (ego death)

Memory suppression (also known as ego suppression, ego dissolution, ego loss or ego death) is defined as an inhibition of a person's ability to maintain a functional short and long-term memory.[59][60][61] This occurs in a manner that is directly proportional to the dosage consumed, and often begins with the degradation of one's short-term memory.

Memory suppression is a process which may be broken down into the 4 basic levels described below:

- Partial short-term memory suppression - At the lowest level, this effect is a partial and potentially inconsistent failure of a person's short-term memory. It can cause effects such as a general difficulty staying focused, an increase in distractibility, and a general tendency to forget what one is thinking or saying.

- Complete short-term memory suppression - At this level, this effect is the complete failure of a person's short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of being completely incapable of remembering any specific details regarding the present situation and the events leading up to it for more than a few seconds. This state of mind can often result in thought loops, confusion, disorientation, and a loss of control, especially for the inexperienced. At this level, it can also become impossible to follow both conversations and the plot of most forms of media.

- Partial long-term memory suppression - At this level, this effect is the partial, often intermittent failure of a person's long-term memory in addition to the complete failure of their short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of an increased difficulty recalling basic concepts and autobiographical information from one's long-term memory. Compounded with the complete suppression of short term memory, it creates an altered state where even basic tasks become challenging or impossible as one cannot mentally access past memories of how to complete them.

For example, one may take a longer time to recall the identity of close friends or temporarily forget how to perform basic tasks. This state may create the sensation of experiencing something for the first time. At this stage, a reduction of certain learned personality traits, awareness of cultural norms, and linguistic recall may accompany the suppression of long-term memory.

- Complete long-term memory suppression - At the highest level, this effect is the complete and persistent failure of both a person's long and short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of becoming completely incapable of remembering even the most basic fundamental concepts stored within the person's long-term memory. This includes everything from their name, hometown, past memories, the awareness of being on drugs, what drugs even are, what human beings are, what life is, that time exists, what anything is, or that anything exists.

Memory suppression of this level blocks all mental associations, attached meaning, acquired preferences, and value judgements one may have towards the external world. Sufficiently intense memory loss is also associated with the loss of a sense of self, in which one is no longer aware of their own existence. In this state, the user is unable to recall all learned conceptual knowledge about themselves and the external world, and no longer experiences the sensation of being a separate observer in an external world. This experience is commonly referred to as "ego death".

Memory suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought loops, personal bias suppression, amnesia, and delusions. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.[62]

It is worth noting that although memory suppression is vaguely similar in its effects to amnesia, it differs in that it directly suppresses one's usage of their long or short term memory without inhibiting the person's ability to recall what happened during this experience afterward. In contrast, amnesia does not directly affect the usage of one's short or long-term memory during its experience but instead renders a person incapable of recalling events after it has worn off. A person experiencing memory suppression cannot access their existing memory, while a person with drug-induced amnesia cannot properly store new memories. As such, a person experiencing amnesia may not obviously appear to be doing so, as they can often carry on normal conversations and perform complex tasks. This is not the case with memory suppression.

Anxiety suppression

Anxiety suppression (also known as anxiolysis or minimal sedation)[63] is medically recognized as a partial to complete suppression of a person’s ability to feel anxiety, general unease, and negative feelings of both psychological and physiological tension.[64] The experience of this effect may decrease anxiety-related behaviours such as restlessness, muscular tension,[65] rumination, and panic attacks. Complete anxiety suppression can produce feelings of extreme calmness and relaxation; however, it can also lead to undesirable outcomes when accompanied by other effects such as disinhibition or sedation.

It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of anxiolytic compounds which primarily include GABAergic depressants,[66][67] such as benzodiazepines,[68] alcohol,[69] GHB,[70] and gabapentinoids[71]. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of a large variety of other pharmacological classes which include but are not limited to cannabinoids,[72] dissociatives,[73] SSRIs, and opioids.

Disinhibition

Disinhibition is medically recognized as an orientation towards immediate gratification, leading to impulsive behavior driven by current thoughts, feelings, and external stimuli, without regard for past learning or consideration of future consequences.[74][75][76] This is usually manifested through recklessness, poor risk assessment, and a disregard for social conventions.

At its lower levels of intensity, disinhibition can allow one to overcome emotional apprehension and suppressed social skills in a manner that is moderated and controllable for the average person. This can often prove useful for those who suffer from social anxiety or a general lack of self-confidence.

However, at higher levels of intensity, the disinhibited individual may be completely unable to maintain any semblance of self-restraint, at the expense of politeness, sensitivity, social appropriateness, or local laws and regulations. This lack of constraint can be negative, neutral, or positive depending on the individual and their current environment. The negative consequences of disinhibited behaviour range from relatively benign consequences (such as embarrassing oneself) to destructive and damaging ones (such as driving under the influence or committing criminal acts).

Disinhibition is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as amnesia and anxiety suppression in a manner which can further decrease the person's observance of and regard for social norms. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of GABAergic depressants, such as alcohol,[77] benzodiazepines,[78] phenibut, and GHB. However, it may also occur under the influence of certain stimulants,[79] entactogens,[80] and dissociatives[81].

Dream suppression

Dream suppression is defined as a decrease in the vividness, intensity, frequency, and recollection of a person's dreams. At its lower levels, this can be a partial suppression which results in the person having dreams of a lesser intensity and a lower rate of frequency. However, at its higher levels, this can be a complete suppression which results in the person not experiencing any dreams at all.

Dream suppression is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of cannabinoids[82] and most types of antidepressants[83][84][85]. This is due to the way in which they increase REM latency, decrease REM sleep, reduce total sleep time and efficiency, and increase wakefulness.[82][83][84][86] REM sleep is where the majority of dreams occur.[87]

Cognitive exhaustion

Cognitive fatigue (also called exhaustion, tiredness, lethargy, languidness, languor, lassitude, and listlessness) is medically recognized as a state usually associated with a weakening or depletion of one's mental resources.[88][89] The intensity and duration of this effect typically depends on the substance consumed and its dosage. It can also be further exacerbated by various factors such as a lack of sleep[90] or food[91]. These feelings of exhaustion involve a wide variety of symptoms which generally include some or all of the following effects:

- Analysis depression

- Motivation depression

- Thought deceleration

- Short term memory suppression

- Thought disorganization

- Language depression

- Creativity depression

Cognitive fatigue is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of antipsychotic compounds,[92][93] such as quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone. However, it can also occur during the withdrawal symptoms of many depressants,[94] and during the offset of many stimulants[95].

Enhancements

Novelty enhancement

Novelty enhancement is defined as a feeling of increased fascination[96], awe,[96][97][98] and appreciation[98][99] attributed to specific parts or the entirety of one's external environment. This can result in an often overwhelming impression that everyday concepts such as nature, existence, common events, and even household objects are now considerably more profound, interesting, and significant.[100][101]

The experience of this effect commonly forces those who undergo it to acknowledge, consider, and appreciate the things around them in a level of detail and intensity which remains largely unparalleled throughout every day sobriety. It is often generally described using phrases such as "a sense of wonder"[96][98] or "seeing the world as new".[99]

Novelty enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression, emotion intensification and spirituality intensification in a manner which further intensifies the experience. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, dissociatives, and entactogens.

Current mind state enhancement

Emotion intensification (also known as affect intensification)[102] is defined as an increase in a person's current emotional state beyond normal levels of intensity.[103][104][105]

Unlike many other subjective effects such as euphoria or anxiety, this effect does not actively induce specific emotions regardless of a person's current state of mind and mental stability. Instead, it works by passively amplifying and enhancing the genuine emotions that a person is already feeling prior to ingesting the drug or prior to the onset of this effect. This causes emotion intensification to be equally capable of manifesting in both a positive and negative direction.[102][103][105][106][101] This effect highlights the importance of set and setting when using psychedelics in a therapeutic context, especially if the goal is to produce a catharsis.[102][104][101]

For example, an individual who is currently feeling somewhat anxious or emotionally unstable may become overwhelmed with intensified negative emotions, paranoia, and confusion. In contrast, an individual who is generally feeling positive and emotionally stable is more likely to find themselves overwhelmed with states of emotional euphoria, happiness, and feelings of general contentment. The intensity of emotional states felt under emotion intensification can shape the tone of a trip and predispose the user to other effects, such as mania or unity in positive states and thought loops or feelings of impending doom in negative states.[105] Intense negative or difficult emotions may still arise in therapeutic contexts, however (with adequate support) people nevertheless view the experience positively due to the perceived value of integrating the emotional states' additional insight.[102][101]

Emotion intensification is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[102][103][104][105][101] However, it can also occur under the influence of cannabinoids, GABAergic depressants,[107][108] and stimulants.[106][109]

Thought acceleration

Thought acceleration (also known as racing thoughts)[110] is defined as the experience of thought processes being sped up significantly in comparison to that of everyday sobriety.[111][112] When experiencing this effect, it will often feel as if one rapid-fire thought after the other is being generated in incredibly quick succession. Thoughts while undergoing this effect are not necessarily qualitatively different, but greater in their volume and speed. However, they are commonly associated with a change in mood that can be either positive or negative.[110][113]

Thought acceleration is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, anxiety, and analysis enhancement in a manner which not only increases the speed of thought, but also significantly enhances the sharpness of a person's mental clarity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil, and MDMA. However, it can also occur under the influence of certain stimulating psychedelics such as LSD, 2C-E, DOC, AMT.

Thought connectivity

Thought connectivity is defined as an alteration of a person's thought stream which is characterized by a distinct increase in unconstrained wandering thoughts which connect into each other through a fluid association of ideas.[105][61][114][115] During this state, thoughts may be subjectively experienced as a continuous stream of vaguely related ideas which tenuously connect into each other by incorporating a concept that was contained within the previous thought. When experienced, it is often likened to a complex game of word association.

During this state, it is often difficult for the person to consciously guide the direction of their thoughts in a manner that leads into a state of increased distractibility.[105] This will usually also result in one's train of thought contemplating an extremely broad variety of subjects, which can range from important, trivial, insightful, and nonsensical topics.

Thought connectivity is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought acceleration and creativity enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of dissociatives, stimulants, and cannabinoids.

Analysis enhancement

Analysis enhancement is defined as a perceived improvement of a person's overall ability to logically process information[116][117][118] or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios. This effect can lead to a deep state of contemplation which often results in an abundance of new and insightful ideas. It can give the person a perceived ability to better analyze concepts and problems in a manner which allows them to reach new conclusions, perspectives, and solutions which would have been otherwise difficult to conceive of.

Although this effect will often result in deep states of introspection, in other cases it can produce states which are not introspective but instead result in a deep analysis of the exterior world, both taken as a whole and as the things which comprise it. This can result in a perceived abundance of insightful ideas and conclusions with powerful themes pertaining to what is often described as "the bigger picture". These ideas generally involve (but are not limited to) insight into philosophy, science, spirituality, society, culture, universal progress, humanity, loved ones, the finite nature of our lives, history, the present moment, and future possibilities.

Cognitive performance is undeniably linked to personality,[119] and it has been repeatedly shown that psychedelics alter a user's personality for the long term. Experienced psychedelics users score significantly better than controls on several psychometric measures.[120]

Analysis enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, conceptual thinking, and thought connectivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, nicotine, and caffeine.[116][118] However, it can also occur in a more powerful although less consistent form under the influence of psychedelics such as certain LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[120]

Rejuvination

Rejuvenation can be described as feelings of mild to extreme cognitive refreshment which are felt during the afterglow of certain compounds. The symptoms of rejuvenation often include a sustained sense of heightened mental clarity, increased emotional stability, increased calmness, mindfulness, increased motivation, personal bias suppression, increased focus and decreased depression. At its highest level, feelings of rejuvenation can become so intense that they manifest as the profound and overwhelming sensation of being "reborn" anew. This mindstate can potentially last anywhere from several hours to several months after the substance has worn off.

Rejuvination is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Empathy, love and sociability enhancement

Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement is defined as the experience of a mind state which is dominated by intense feelings of compassion, talkativeness, and happiness.[121][122] The experience of this effect creates a wide range of subjective changes to a person's perception of their feelings towards other people and themselves. These are described and documented in the list below:

- Increased sociability and the feeling that communication comes easier and more naturally.

- Increased urge to communicate or express one's affectionate feelings towards others, even if they happen to be strangers.

- Increased feelings of empathy, love, and connection with others.

- Increased motivation to resolve social conflicts and improve interpersonal relationships.

- Decreased negative emotions and mental states such as stress, anxiety, and fear.

- Decreased insecurity, defensiveness, and fear of emotional injury or rejection from others.

- Decreased irritability, aggression, anger, and jealousy.

Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, motivation enhancement, and anxiety suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of entactogenic compounds such as MDMA,[123] 4-FA, and 2C-B.[124] However, it can also subtly occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of GABAergic depressants, and certain stimulants.[109]

Multiple thought streams

Multiple thought streams is defined as a state of mind in which a person has more than one internal narrative or stream of consciousness simultaneously occurring within their head. This can result in any number of independent thought streams occurring at the same time, each of which are often controllable in a similar manner to that of one's everyday thought stream.

These multiple coinciding thought streams can be experienced simultaneously in a manner which is evenly distributed and does not prioritize the awareness of any particular thought stream over an other. However, they can also be experienced in a manner which feels as if it brings awareness of a particular thought stream to the foreground while the others continue processing information in the background. This form of multiple thought streams typically swaps between specific trains of thought at seemingly random intervals.

The experience of this effect can sometimes allow one to analyze many different ideas simultaneously and can be a source of great insight. However, it will usually overwhelm the person with an abundance of information that becomes difficult or impossible to fully process at a normal speed.

Multiple thought streams are often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression and thought disorganization. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Focus enhancement

Focus intensification is defined as the experience of an increased ability to selectively concentrate on an aspect of the environment while ignoring other things. It can be best characterized by feelings of intense concentration which can allow one to continuously focus on and perform tasks which would otherwise be considered too monotonous, boring, or dull to not get distracted from.[125][126]

The degree of focus induced by this effect can be much stronger than what a person is capable of sober. It can allow for hours of effortless, single-minded, and continuous focus on a particular activity to the exclusion of all other considerations such as eating and attending to bodily functions. However, although focus intensification can improve a person’s ability to engage in tasks and use time effectively, it is worth noting that it can also cause a person to focus intensely and spend excess time on unimportant activities.

Focus intensification is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as motivation enhancement, thought acceleration, and stimulation. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds such as amphetamine,[127] methylphenidate,[128] modafinil,[129] and caffeine.[130] However, it is worth noting that the same compounds which induce this mind state at moderate dosages will also often result in the opposite effect of focus suppression at heavier dosages.[131]

Sexual arousal

Increased libido can be described as a distinct increase in feelings of sexual desire, the anticipation of sexual activity, and the likelihood that a person will view the context of a given situation as sexual in nature.[132][133] When experienced, this sensation is not overwhelming or out of control, but simply remains something that one is constantly aware of.

Increased libido is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as tactile intensification, and stimulation in a manner which can lead to greatly intensified feelings of sexual pleasure. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant compounds, particularly dopaminergic stimulants such as methamphetamine[134] and cocaine[135]. However, it may also occur under the influence of other compounds such as GABAergic depressants and psychedelics.

Motivation enhancement

Motivation enhancement is defined as an increased desire to perform tasks and accomplish goals in a productive manner.[136][137][138] This includes tasks and goals that would normally be considered too monotonous or overwhelming to fully commit oneself to.

A number of factors (which often, but not always, co-occur) reflect or contribute to task motivation: namely, wanting to complete a task, enjoying it or being interested in it.[138] Motivation may also be supported by closely related factors, such as positive mood, alertness, energy, and the absence of anxiety. Although motivation is a state, there are trait-like differences in the motivational states that people typically bring to tasks, just as there are differences in cognitive ability.[137]

Motivation enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation and thought acceleration in a manner which further increases one's productivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine,[137][139] methylphenidate,[137] nicotine,[140] and modafinil.[141] However, it may also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of certain opioids,[142][143] and GABAergic depressants.[142]

Memory enhancement

Memory enhancement is defined as an improvement in a person's ability to recall or retain memories.[144][145][146][147] The experience of this effect can make it easier for a person to access and remember past memories at a greater level of detail when compared to that of everyday sober living. It can also help one retain new information that may then be more easily recalled once the person is no longer under the influence of the psychoactive substance.

Memory enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis enhancement and thought acceleration. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as methylphenidate,[148] caffeine,[146] Noopept,[149] nicotine,[150] and modafinil.[151]

Types

Different substances can enhance different kinds of memory with some considerable overlap. Generally, there are three types:

- Long-term memory: A vast store of knowledge and a record of prior events.[152]

- Short-term memory: Faculties of the human mind that can hold a limited amount of information in a very accessible state temporarily.[152][153][154]

- Working memory: Information used to plan and carry out behavior. Not completely distinct from short-term memory, it's generally viewed as the combination of multiple components working together. Measures of working memory have been found to correlate with intellectual aptitudes (and especially fluid intelligence) better than measures of short-term memory and, in fact, possibly better than measures of any other particular psychological process. Both storage and processing have to be engaged concurrently to assess working memory capacity, which relates it to cognitive aptitude.[152][153][154][155][156]

Ego inflation

Ego inflation is defined as an effect that magnifies and intensifies one's own ego and self-regard in a manner which results in feeling an increased sense of confidence, superiority, and general arrogance.[157] During this state, it can often feel that one is considerably more intelligent, important, and capable in comparison to those around them. This occurs in a manner which is similar to the psychiatric condition known as narcissistic personality disorder.[158]

At lower levels, this experience can result in an enhanced ability to handle social situations due to a heightened sense of confidence.[159] However, at higher levels, it can result in a reduced ability to handle social situations due to magnifying egoistic behavioural traits that may come across as distinctly obnoxious, narcissistic, and selfish to other people.

It is worth noting that regular and repeated long-term exposure to this effect can leave certain individuals with persistent behavioural traits of ego inflation, even when sober, within their day to day life.

Ego inflation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as disinhibition, irritability, and paranoia in a manner which can lead to destructive behaviors and violent tendencies.[159] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant compounds, particularly dopaminergic stimulants such as amphetamines, and cocaine.[157][159][160][161] However, it may also occur under the influence of other compounds such as GABAergic depressants[157] and certain dissociatives.

Dream potentiation

Dream potentiation is defined as an effect which increases the subjective intensity, vividness, and frequency of sleeping dream states.[162][163] This effect also results in dreams having a more complex and incohesive plot with a higher level of detail and definition.[163] Additionally, the effect causes a greatly increased likelihood of them becoming lucid dreams.

Dream potentiation is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of oneirogenic compounds, a class of hallucinogen that is used to specifically potentiate dreams when taken before sleep. However, it can also occur as a residual side effect from falling asleep under the influence of an extremely wide variety of substances. At other times, it can occur as a relatively persistent effect that has arisen as a symptom of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD).

Spirituality enhancement

Spirituality intensification is defined as the experience of a shift in a person’s personal beliefs regarding their existence and place within the universe, their relationship to others, and what they value as meaningful in life. It results in a person rethinking the significance they place on certain key concepts, holding some in higher regard than they did previously, and dismissing others as less important.[164] These concepts and notions are not limited to but generally include:

- An increased sense of personal purpose.[165]

- An increased interest in the pursuit of developing personal religious and spiritual ideologies.[166][167]

- The formation of complex personal religious beliefs.

- An increased sense of compassion towards nature and other people.[166][167][168]

- An increased sense of unity and interconnectedness between oneself, nature, "god", and the universe as a whole.[164][166][168][169][170][171][172]

- A decreased sense of value placed upon money and material objects.[168]

- A decreased fear and greater acceptance of death and the finite nature of existence.[164][173][174]

Although difficult to fully specify due to the subjective aspect of spirituality intensification, these changes in to a person's belief system can often result in profound changes in a person's personality[168][170][175] which can sometimes be distinctively noticeable to the people around those who undergo it. This shift can occur suddenly but will usually increase gradually over time as a person repeatedly uses the psychoactive substance which is inducing it.

Spirituality intensification is unlikely to be an isolated effect component but rather the result of a combination of an appropriate setting[166] in conjunction with other coinciding effects such as analysis enhancement, autonomous voice communication, novelty enhancement, perception of interdependent opposites, perception of predeterminism, perception of self-design, personal bias suppression, and unity and interconnectedness. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of dissociatives, such as ketamine, PCP, and DXM.

Novel states

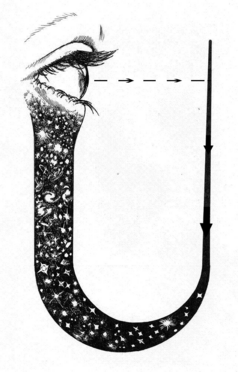

Time distortion

Time distortion is defined as an effect that makes the passage of time feel difficult to keep track of and wildly distorted.[176] It is usually felt in two different forms, time dilation and time compression.[177] These two forms are described and documented below:

Time dilation

Time dilation is defined as the feeling that time has slowed down.[178] This commonly occurs during intense hallucinogenic experiences and seems to stem from the fact that during an intense trip, abnormally large amounts of experience are felt in very short periods of time.[179][180] This can create the illusion that more time has passed than actually has. For example, at the end of certain experiences, one may feel that they have subjectively undergone days, weeks, months, years, or even infinite periods of time.

Time dilation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as spirituality intensification,[181] thought loops, novelty enhancement, and internal hallucinations in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately large number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[182][183] dissociatives, entactogens,[184][185] and cannabinoids.

Time compression

Time compression is defined as the experience of time speeding up and passing much quicker than it usually would while sober. For example, during this state a person may realize that an entire evening has passed them by in what feels like only a couple of hours.

This commonly occurs under the influence of certain stimulating compounds and seems to at least partially stem from the fact that during intense levels of stimulation, people typically become hyper-focused on activities and tasks in a manner which can allow time to pass them by without realizing it. However, the same experience can also occur on depressant compounds which induce amnesia. This occurs due to the way in which a person can literally forget everything that has happened while still experiencing the effects of the substance, thus giving the impression that they have suddenly jumped forward in time.

Time compression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression, focus intensification, stimulation, and amnesia in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately small number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of stimulating and/or amnesic compounds,[186] such as dissociatives,[187] entactogens, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines.

Time reversal

Time reversal is defined as the perception that the events, hallucinations, and experiences that occurred around one's self within the previous several minutes to several hours are spontaneously playing backwards in a manner which is somewhat similar to that of a rewinding VHS tape. During this reversal, the person's cognition and train of thought will typically continue to play forward in a coherent and linear manner while they watch the external environment around them and their body's physical actions play in reverse order. This can either occur in real time, with 5 minutes of time reversal taking approximately 5 minutes to fully rewind, or it can occur in a manner which is sped up, with 5 minutes of time reversal only taking less than a minute. It can reasonably be speculated that the experience of time reversal may potentially occur through a combination of internal hallucinations and errors in memory encoding.

Time reversal is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as internal hallucinations, thought loops, and deja vu. It is most commonly induced under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.

Analysis enhancement

Analysis enhancement is defined as a perceived improvement of a person's overall ability to logically process information[116][117][118] or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios. This effect can lead to a deep state of contemplation which often results in an abundance of new and insightful ideas. It can give the person a perceived ability to better analyze concepts and problems in a manner which allows them to reach new conclusions, perspectives, and solutions which would have been otherwise difficult to conceive of.

Although this effect will often result in deep states of introspection, in other cases it can produce states which are not introspective but instead result in a deep analysis of the exterior world, both taken as a whole and as the things which comprise it. This can result in a perceived abundance of insightful ideas and conclusions with powerful themes pertaining to what is often described as "the bigger picture". These ideas generally involve (but are not limited to) insight into philosophy, science, spirituality, society, culture, universal progress, humanity, loved ones, the finite nature of our lives, history, the present moment, and future possibilities.

Cognitive performance is undeniably linked to personality,[119] and it has been repeatedly shown that psychedelics alter a user's personality for the long term. Experienced psychedelics users score significantly better than controls on several psychometric measures.[120]

Analysis enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, conceptual thinking, and thought connectivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, nicotine, and caffeine.[116][118] However, it can also occur in a more powerful although less consistent form under the influence of psychedelics such as certain LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[120]

Deja-Vu

Déjà Vu (or Deja Vu) is defined as as any sudden inappropriate impression of familiarity of a present experience with an undefined past.[188][189][190][191] Its two critical components are an intense feeling of familiarity, and a certainty that the current moment is novel.[192] This term is a common phrase from the French language which translates literally into “already seen”. It is a well-documented phenomenon that can commonly occur throughout both sober living and under the influence of hallucinogens.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, many compounds are commonly capable of inducing spontaneous and often prolonged states of mild to intense sensations of déjà vu. This can provide one with an overwhelming sense that they have “been here before”. The sensation is also often accompanied by a feeling of familiarity with the current location or setting, the current physical actions being performed, the situation as a whole, or the effects of the substance itself.

This effect is often triggered despite the fact that during the experience of it, the person can be rationally aware that the circumstances of the “previous” experience (when, where, and how the earlier experience occurred) are uncertain or believed to be impossible.

Déjà vu is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as olfactory hallucinations and derealization.[193] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[194] such as psychedelics,[195] cannabinoids,[196] and dissociatives.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness can be described as a psychological concept which is well established within the scientific literature and commonly discussed in association with meditation.[197][198]

It is often broken down into two separate subcomponents which comprise this effect: The first of these components involves the self-regulation of attention so that its focus is completely directed towards immediate experience, thereby quietening one's internal narrative and allowing for increased recognition of external and mental events within the present moment.[199][200] The second of these components involves adopting a particular orientation toward one’s experiences in the present moment that is characterized by a lack of judgement, curiosity, openness, and acceptance.[201]

Within meditation, this state of mind is deliberately practised and maintained via the conscious and manual redirection of one's awareness towards a singular point of focus for extended periods of time. However, within the context of psychoactive substance usage, this state is often spontaneously induced without any conscious effort or the need of any prior knowledge regarding meditative techniques.

Mindfulness is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety suppression and focus intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids. However, it can also occur on entactogens, certain nootropics such as l-theanine, and during simultaneous doses of benzodiazepines and stimulants.

Feelings of predeterminism

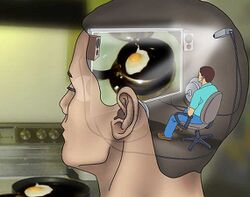

Perception of predeterminism can be described as the sensation that all physical and mental processes are the result of prior causes, that every event and choice is an inevitable outcome that could not have happened differently, and that all of reality is a complex causal chain that can be traced back to the beginning of time. This is accompanied by the absence of the feeling that a person's decision-making processes and general cognitive faculties inherently possess "free will”. This sudden change in perspective causes the person to feel as if their personal choices, physical actions, and individual personality traits have always been completely predetermined by prior causes and are, therefore, outside of their conscious control.

During this state, a person begins to feel as if their decisions arise from a complex set of internally stored, pre-programmed, and completely autonomous, instant electrochemical responses to perceived sensory input. These sensations are often interpreted as somehow disproving the concept of free will, as the experience of this effect feels as if it is fundamentally incompatible with the notion of being self-determined. This state can also lead a person to the conclusion that their very identity and selfhood are the cumulative results of their biology and past experiences.

Once the effect begins to wear off, a person will often return to their everyday feelings of freedom and independence. Despite this, however, they will often retain realizations regarding what is often interpreted as a profound insight into the apparent illusory nature of free will.

Perception of predeterminism is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as ego dissolution and physical autonomy. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Conceptual thinking

Conceptual thinking is defined as an alteration to the nature and content of one's internal thought stream. This alteration predisposes a user to think thoughts which are no longer primarily comprised of words and linear sentence structures. Instead, thoughts become equally comprised of what is perceived to be incredibly detailed renditions of the innately understandable and internally stored concepts for which no words exist. Thoughts cease to be spoken by an internal narrator and are instead “felt” and intuitively understood.

For example, if a person was to think of an idea such as a "chair" during this state, one would not hear the word as part of an internal thought stream, but would feel the internally stored, pre-linguistic and innately understandable data which comprises the specific concept labelled within one's memory as a "chair". These conceptual thoughts are felt in a comprehensive level of detail that feels as if it is unparalleled within the primarily linguistic thought structure of everyday life. This is sometimes interpreted by those who undergo it as some "higher level of understanding".

During this experience, conceptual thinking can cause one to feel not just the entirety of a concept's attributed data, but also how a given concept relates to and depends upon other known concepts. This can result in the perception that the person can better comprehend the complex interplay between the idea that is being contemplated and how it relates to other ideas.

Conceptual thinking is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression and analysis enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Subconscious communication

Autonomous voice communication (also known as auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs))[202] is defined as the experience of being able to hear and converse with a disembodied and audible voice of unknown origin which seemingly resides within one's own head.[203][204][205][206] This voice is often capable of high levels of complex and detailed speech which are typically on par with the intelligence and vocabulary of ones own conversational abilities.

As a whole, the effect itself can be broken down into 5 distinct levels of progressive intensity, each of which are described below:

- A sensed presence of the other - The distinctive feeling that another form of consciousness is internally present alongside that of one's usual sense of self. This sensation is often referred to within the scientific literature as a "sense of presence".[204][207][208][209]

- Mutually generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are partially generated by one's own thought stream and in equal measure by that of a separate thought stream.[210]

- Separately generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are generated by an entirely distinct and separate thought stream that resides within one's head.[202][204][210]

- Separately generated audible internal responses - Internally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice within one's head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to one's own spoken voice.[203][210]

- Separately generated audible external responses - Externally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice which sounds as if it is coming from outside one's own head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to the person's own spoken voice.[203][204][210]

The speaker behind this voice is commonly interpreted by those who experience it to be the voice of their own subconscious, the psychoactive substance itself, a specific autonomous entity, or even supernatural concepts such as god, spirits, souls, and ancestors.

At higher levels, the conversational style of that which is discussed between both the voice and its host can be described as essentially identical in terms of its coherency and linguistic intelligibility as that of any other everyday interaction between the self and another human being of any age with which one might engage in conversation with. Higher levels may also manifest itself in multiple voices or even an ambiguous collection of voices such as a crowd.[204]

However, there are some subtle but identifiable differences between this experience and that of normal everyday conversations. These stem from the fact that one's specific set of knowledge, memories and experiences are identical to that of the voice which is being communicated with.[204][206] This results in conversations in which both participants often share an identical vocabulary down to the very use of their colloquial slang and subtle mannerisms. As a result of this, no matter how in-depth and detailed the discussion becomes, no entirely new information is ever exchanged between the two communicators. Instead, the discussion focuses primarily on building upon old ideas and discussing new opinions or perspectives regarding the previously established content of one's life.

Autonomous voice communication is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as delusions, autonomous entities, auditory hallucinations, and psychosis in a manner which can sometimes lead the person into believing the voices' statements unquestionably in a delusional manner. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. However, it may also occur during the offset of prolonged stimulant binges and less consistently under the influence of heavy dosages of cannabinoids.

Personality regression

Personality regression is a mental state in which one suddenly adopts an identical or similar personality, thought structure, mannerisms and behaviours to that of their past self from a younger age.[211] During this state, the person will often believe that they are literally a child again and begin outwardly exhibiting behaviours which are consistent to this belief. These behaviours can include talking in a childlike manner, engaging in childish activities, and temporarily requiring another person to act as a caregiver or guardian. There are also anecdotal reports of people speaking in languages which they have not used for many years under the influence of this effect.[212]

Personality regression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, memory suppression, and ego dissolution. It is a relatively rare effect that is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, most notably Ayahuasca, LSD and Ibogaine in particular as well as certain dissociatives. However, it can also occur for people during times of stress,[211] as a response to childhood trauma, as a symptom of borderline personality disorder,[213] or as a regularly reoccuring facet of certain peoples lives that is not necessarily associated with any psychological problems.

Thought loops

A thought loop is defined as the experience of becoming trapped within a chain of thoughts, actions and emotions which repeats itself over and over again in a cyclic loop. These loops usually range from anywhere between 5 seconds and 2 minutes in length. However, some users have reported them to be up to a few hours in length. It can be extremely disorientating to undergo this effect and it often triggers states of progressive anxiety within people who may be unfamiliar with the experience. The most effective way to end a cycle of thought loops is to simply sit down and try to let go.

This state of mind is most likely to occur during states of memory suppression in which there is a partial or complete failure of the person's short-term memory. This may suggest that thought loops are the result of cognitive processes becoming unable to sustain themselves for appropriate lengths of time due to a lapse in short-term memory, resulting in the thought process attempting to restart from the beginning only to fall short once again in a perpetual cycle.

Thought loops are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[214] such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of stimulants and benzodiazepines.

Feelings of interdependent opposites

Perception of interdependent opposites can be described as the experience of a powerful subjective feeling that reality is based upon a binary system in which the existence of fundamentally important concepts or situations logically arise from and depend upon the co-existence of their opposite. This perception is not just understood at a cognitive level, but manifests as intuitive sensations which are felt rather than thought by the person.

This experience is usually interpreted as providing a deep insight into the fundamental nature of reality. For example, concepts such as existence and non-existence, life and death, up and down, self and other, light and dark, good and bad, big and small, pleasure and suffering, yes and no, internal and external, hot and cold, young and old, etc are felt to exist as harmonious forces which necessarily contrast their opposite force in a state of equilibrium.

Perception of interdependent opposites is often accompanied by other coinciding transpersonal effects such as ego dissolution, unity and interconnectedness, and perception of eternalism. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Delusions

A delusion is a false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly held despite what almost everyone else believes and despite what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the contrary. The belief is not ordinarily accepted by other members of the person's culture or subculture (i.e., it is not an article of religious faith). When a false belief involves a value judgement, it is regarded as a delusion only when the judgement is so extreme as to defy credibility. Delusional conviction can sometimes be inferred from an overvalued idea (in which case the individual has an unreasonable belief or idea but does not hold it as firmly as is the case with a delusion).[215][216][217]

This article focuses primarily on the types of delusion that are commonly induced by hallucinogens or other psychoactive substances, as opposed to the various categories that are listed within the DSM as occurring within people who suffer from psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Although there are common themes between these two causes of delusion, the underlying circumstances are distinct enough that they are seemingly very different in their themes, behaviour, and frequency of occurrence.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, delusions can usually be broken out of when overwhelming evidence is provided to the contrary or when the person has sobered up enough to logically analyse the situation. It is exceedingly rare for hallucinogen induced delusions to persist into sobriety.

It is also worth noting that delusions can often spread between individuals in group settings.[218] For example, if one person makes a verbal statement regarding a delusional belief they are currently holding while in the presence of other similarly intoxicated people, these other people may also begin to hold the same delusion. This can result in shared hallucinations and a general reinforcement of the level of conviction in which they are each holding the delusional belief.

Delusions are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, deliriants, and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, stimulant psychosis, and sleep deprivation. They are most likely to occur during states of memory suppression and share common themes and elements with clinical schizophrenia.

Unity and interconnectedness

Unity and interconnectedness can be described as the experience of one's sense of self becoming temporarily changed to feel as if it is constituted by a wider array of concepts than that which it previously did. For example, while a person may usually feel that they are exclusively their “ego” or a combination of their “ego” and physical body, during this state their sense of identity can change to also include the external environment or an object they are interacting with. This results in intense and inextricable feelings of unity or interconnectedness between oneself and varying arrays of previously "external" systems.

It is worth noting that many people who undergo this experience consistently interpret it as the removal of a deeply embedded illusion, the destruction of which is often described as some sort of profound “awakening” or “enlightenment.” However, it is important to understand that these conclusions and feelings should not necessarily be accepted at face value as inherently true.

Unity and interconnectedness most commonly occurs under the influence of psychedelic and dissociative compounds such as LSD, DMT, ayahuasca, mescaline, and ketamine. However it can also occur during well-practiced meditation, deep states of contemplation, and intense focus.

There are a total of 5 distinct levels of identity which a person can experience during this state. These various altered states of unity have been arranged into a leveling system that orders its different states from least to the most number of concepts that one's identity is currently attributed to. These levels are described below:

1. Unity between specific "external" systems

At the lowest level, this effect can be described as a perceived sense of unity between two or more systems within the external environment which in everyday life are usually perceived as separate from each other. This is the least complex level of unity, as it is the only level of interconnectedness in which the subjective experience of unity does not involve a state of interconnectedness between the self and the external.

There are an endless number of ways in which this level can manifest, but common examples of the experience often include:

- A sense of unity between specific living things such as animals or plants and their surrounding ecosystems.

- A sense of unity between other human beings and the objects they are currently interacting with.

- A sense of unity between any number of currently perceivable inanimate objects.

- A sense of unity between humanity and nature.

- A sense of unity between literally any combination of perceivable external systems and concepts.

2. Unity between the self and specific "external" systems

At this level, unity can be described as feeling as if one's identity is attributed to (in addition to the body and/or brain) specific external systems or concepts within the immediate environment, particularly those that would usually be considered as intrinsically separate from one's own being.

The experience itself is often described as a loss of perceived boundaries between a person’s identity and the specific physical systems or concepts within the perceivable external environment which are currently the subject of a person's attention. This creates a sensation of becoming inextricably "connected to", "one with", "the same as", or "unified" with whatever the perceived external system happens to be.

There are an endless number of ways in which this level can manifest itself, but common examples of the experience often include:

- Becoming unified with and identifying with a specific object one is interacting with.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with another person or multiple people, particularly common if engaging in sexual or romantic activities.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with the entirety of one's own physical body.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with large crowds of people, particularly common at raves and music festivals.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with the external environment, but not the people within it.

3. Unity between the self and all perceivable "external" systems

At this level, unity can be described as feeling as if one's identity is attributed to the entirety of their immediately perceivable external environment due to a loss of perceived boundaries between the previously separate systems.

The effect creates a sensation in the person that they have become "one with their surroundings.” This is felt to be the result of a person’s sense of self becoming attributed to not just primarily the internal narrative of the ego, but in equal measure to the body itself and everything around it which it is physically perceiving through the senses. It creates the compelling perspective that one is the external environment experiencing itself through a specific point within it, namely the physical sensory perceptions of the body that one's consciousness is currently residing in.

It is at this point that a key component of the high-level unity experience becomes an extremely noticeable factor. Once a person's sense of self has become attributed to the entirety of their surroundings, this new perspective completely changes how it feels to physically interact with what was previously felt to be an external environment. For example, when one is not in this state and is interacting with a physical object, it typically feels as though one is a central agent acting on the separate world around them. However, while undergoing a state of unity with the currently perceivable environment, interacting with an external object consistently feels as if the whole unified system is autonomously acting on itself with no central, separate agent operating the process of interaction. Instead, the process suddenly feels as if it has become completely decentralized and holistic, as the environment begins to autonomously and harmoniously respond to itself in a predetermined manner to perform the interaction carried out by the individual.

4. Unity between the self and all known "external" systems

At the highest level, this effect can be described as feeling as if one's identity is simultaneously attributed to the entirety of the immediately perceivable external environment and all known concepts that exist outside of it. These known concepts typically include all of humanity, nature, and the universe as it presently stands in its complete entirety. This feeling is commonly interpreted by people as "becoming one with the universe".

When experienced, the effect creates the sudden perspective that one is not a separate agent approaching an external reality, but is instead the entire universe as a whole experiencing itself, exploring itself, and performing actions upon itself through the specific point in space and time which this particular body and conscious perception happens to currently reside within. People who undergo this experience consistently interpret it as the removal of a deeply embedded illusion, with the revelation often described as some sort of profound “awakening” or “enlightenment.”

Although they are not necessarily literal truths about reality, at this point, many commonly reported conclusions of a religious and metaphysical nature often begin to manifest themselves as profound realizations. These are described and listed below:

- The sudden and total acceptance of death as a fundamental complement of life. Death is no longer felt to be the destruction of oneself, but simply the end of this specific point of a greater whole, which has always existed and will continue to exist and live on through everything else in which it resides. Therefore, the death of a small part of the whole is seen as an inevitable, and not worthy of grief or any emotional attachment, but simply a fact of reality.

- The subjective perspective that one's preconceived notions of "god" or deities can be felt as identical to the nature of existence and the totality of its contents, including oneself. This typically entails the intuition that if the universe contains all possible power (omnipotence), all possible knowledge (omniscience), is self-creating, and self-sustaining then on either a semantic or literal level the universe and its contents could also be viewed as a god.

- The subjective perspective that one, by nature of being the universe, is personally responsible for the design, planning, and implementation of every single specific detail and plot element of one's personal life, the history of humanity, and the entirety of the universe. This naturally includes personal responsibility for all humanity's sufferings and flaws but also includes its acts of love and achievements.

Euphoria

Cognitive euphoria (semantically the opposite of cognitive dysphoria) is medically recognized as a cognitive and emotional state in which a person experiences intense feelings of well-being, elation, happiness, excitement, and joy.[219] Although euphoria is an effect (i.e. a substance is euphorigenic),[220][221] the term is also used colloquially to define a state of transcendent happiness combined with an intense sense of contentment.[222] However, recent psychological research suggests euphoria can largely contribute to but should not be equated with happiness.[223]

Cognitive euphoria is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as physical euphoria and tactile intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of opioids, entactogens, stimulants, and GABAergic depressants. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids.

Depression

Depression medically encompasses a variety of different mood disorders whose common features are a sad, empty, or irritable mood accompanied by bodily and cognitive changes that significantly affect an individual's ability to function.[224][225] These different mood disorders have different durations, timing, or presumed origin. Differentiating normal sadness/grief from a depressive episode requires a careful and meticulous examination. For example, the death of a loved one may cause great suffering, but it does not typically produce a medically defined depressive episode.[224]

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, depressivity is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, irritability and dysphoria. It is most commonly induced through prolonged chronic stimulant or depressant use, during the withdrawal symptoms of almost any substance, or during the comedown/crash of a stimulant. It is associated specifically with higher alcohol consumption.[226] However, it is worth noting that substance-induced depressivity is often much shorter lasting than clinical depression, usually subsiding once the effects or withdrawal symptoms of a drug have ended.

If you suspect you are experiencing symptoms of depression, it is highly recommended to seek therapeutic medical attention and/or a support group. Additionally, you may want to read the depression reduction effect.

Depression as an effect has an unfortunate non-specific definition. There are several other relevant terms which should be taken into account when trying to understand this state of mind. These are listed and described.

Anxiety

Anxiety is medically recognized as the experience of negative feelings of apprehension, worry, and general unease.[227][228] These feelings can range from subtle and ignorable to intense and overwhelming enough to trigger panic attacks or feelings of impending doom. Anxiety is often accompanied by nervous behaviour such as stimulation, restlessness, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and muscular tension.[229] Psychoactive substance-induced anxiety can be caused as an inescapable effect of the drug itself, by a lack of experience with the substance or its intensity, as an intensification of a pre-existing state of mind, or by the experience of negative hallucinations. The focus of anticipated danger can be internally or externally derived.