Cognitive effects - Psychedelics: Difference between revisions

>Oskykins m Text replace - "Cognitive effects: Thought loops" to "Thought loops" |

>Oskykins m Text replace - "Cognitive effects: Deja-Vu" to "Deja-Vu" |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

{{:Rejuvenation}} | {{:Rejuvenation}} | ||

==Deja-Vu== | ==Deja-Vu== | ||

{{ | {{:Deja-Vu}} | ||

==Mindfulness== | ==Mindfulness== | ||

{{:Mindfulness}} | {{:Mindfulness}} | ||

Revision as of 02:04, 27 September 2014

This article attempts to break down the cognitive and behavioural effects contained within the psychedelic experience into simple, easy to understand titles, descriptions and levelling systems. This will be done without depending on metaphors, analogies or personal trip reports. The article starts off with descriptions of the simpler effects and works its way up towards more complex experiences as it progresses.

Current mind state enhancement

Emotion intensification (also known as affect intensification)[1] is defined as an increase in a person's current emotional state beyond normal levels of intensity.[2][3][4]

Unlike many other subjective effects such as euphoria or anxiety, this effect does not actively induce specific emotions regardless of a person's current state of mind and mental stability. Instead, it works by passively amplifying and enhancing the genuine emotions that a person is already feeling prior to ingesting the drug or prior to the onset of this effect. This causes emotion intensification to be equally capable of manifesting in both a positive and negative direction.[1][2][4][5][6] This effect highlights the importance of set and setting when using psychedelics in a therapeutic context, especially if the goal is to produce a catharsis.[1][3][6]

For example, an individual who is currently feeling somewhat anxious or emotionally unstable may become overwhelmed with intensified negative emotions, paranoia, and confusion. In contrast, an individual who is generally feeling positive and emotionally stable is more likely to find themselves overwhelmed with states of emotional euphoria, happiness, and feelings of general contentment. The intensity of emotional states felt under emotion intensification can shape the tone of a trip and predispose the user to other effects, such as mania or unity in positive states and thought loops or feelings of impending doom in negative states.[4] Intense negative or difficult emotions may still arise in therapeutic contexts, however (with adequate support) people nevertheless view the experience positively due to the perceived value of integrating the emotional states' additional insight.[1][6]

Emotion intensification is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[1][2][3][4][6] However, it can also occur under the influence of cannabinoids, GABAergic depressants,[7][8] and stimulants.[5][9]

Thought acceleration

Thought acceleration (also known as racing thoughts)[10] is defined as the experience of thought processes being sped up significantly in comparison to that of everyday sobriety.[11][12] When experiencing this effect, it will often feel as if one rapid-fire thought after the other is being generated in incredibly quick succession. Thoughts while undergoing this effect are not necessarily qualitatively different, but greater in their volume and speed. However, they are commonly associated with a change in mood that can be either positive or negative.[10][13]

Thought acceleration is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, anxiety, and analysis enhancement in a manner which not only increases the speed of thought, but also significantly enhances the sharpness of a person's mental clarity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil, and MDMA. However, it can also occur under the influence of certain stimulating psychedelics such as LSD, 2C-E, DOC, AMT.

Thought connectivity

Thought connectivity is defined as an alteration of a person's thought stream which is characterized by a distinct increase in unconstrained wandering thoughts which connect into each other through a fluid association of ideas.[4][14][15][16] During this state, thoughts may be subjectively experienced as a continuous stream of vaguely related ideas which tenuously connect into each other by incorporating a concept that was contained within the previous thought. When experienced, it is often likened to a complex game of word association.

During this state, it is often difficult for the person to consciously guide the direction of their thoughts in a manner that leads into a state of increased distractibility.[4] This will usually also result in one's train of thought contemplating an extremely broad variety of subjects, which can range from important, trivial, insightful, and nonsensical topics.

Thought connectivity is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought acceleration and creativity enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of dissociatives, stimulants, and cannabinoids.

Feelings of fascination, importance and awe

Novelty enhancement is defined as a feeling of increased fascination[17], awe,[17][18][19] and appreciation[19][20] attributed to specific parts or the entirety of one's external environment. This can result in an often overwhelming impression that everyday concepts such as nature, existence, common events, and even household objects are now considerably more profound, interesting, and significant.[21][6]

The experience of this effect commonly forces those who undergo it to acknowledge, consider, and appreciate the things around them in a level of detail and intensity which remains largely unparalleled throughout every day sobriety. It is often generally described using phrases such as "a sense of wonder"[17][19] or "seeing the world as new".[20]

Novelty enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression, emotion intensification and spirituality intensification in a manner which further intensifies the experience. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, dissociatives, and entactogens.

Time distortion

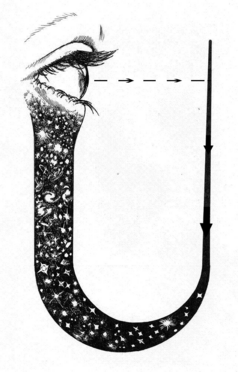

Time distortion is defined as an effect that makes the passage of time feel difficult to keep track of and wildly distorted.[22] It is usually felt in two different forms, time dilation and time compression.[23] These two forms are described and documented below:

Time dilation

Time dilation is defined as the feeling that time has slowed down.[24] This commonly occurs during intense hallucinogenic experiences and seems to stem from the fact that during an intense trip, abnormally large amounts of experience are felt in very short periods of time.[25][26] This can create the illusion that more time has passed than actually has. For example, at the end of certain experiences, one may feel that they have subjectively undergone days, weeks, months, years, or even infinite periods of time.

Time dilation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as spirituality intensification,[27] thought loops, novelty enhancement, and internal hallucinations in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately large number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[28][29] dissociatives, entactogens,[30][31] and cannabinoids.

Time compression

Time compression is defined as the experience of time speeding up and passing much quicker than it usually would while sober. For example, during this state a person may realize that an entire evening has passed them by in what feels like only a couple of hours.

This commonly occurs under the influence of certain stimulating compounds and seems to at least partially stem from the fact that during intense levels of stimulation, people typically become hyper-focused on activities and tasks in a manner which can allow time to pass them by without realizing it. However, the same experience can also occur on depressant compounds which induce amnesia. This occurs due to the way in which a person can literally forget everything that has happened while still experiencing the effects of the substance, thus giving the impression that they have suddenly jumped forward in time.

Time compression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression, focus intensification, stimulation, and amnesia in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately small number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of stimulating and/or amnesic compounds,[32] such as dissociatives,[33] entactogens, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines.

Time reversal

Time reversal is defined as the perception that the events, hallucinations, and experiences that occurred around one's self within the previous several minutes to several hours are spontaneously playing backwards in a manner which is somewhat similar to that of a rewinding VHS tape. During this reversal, the person's cognition and train of thought will typically continue to play forward in a coherent and linear manner while they watch the external environment around them and their body's physical actions play in reverse order. This can either occur in real time, with 5 minutes of time reversal taking approximately 5 minutes to fully rewind, or it can occur in a manner which is sped up, with 5 minutes of time reversal only taking less than a minute. It can reasonably be speculated that the experience of time reversal may potentially occur through a combination of internal hallucinations and errors in memory encoding.

Time reversal is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as internal hallucinations, thought loops, and deja vu. It is most commonly induced under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.

Introspection

Increased introspection is a metacognitive effect defined as the state of mind in which a person feels encouraged to reflect upon and examine their internal psychological processes, judgements, or perceptions.[34][35][36][37][38][39] Questions such as "Why am I feeling so?", "How can I describe it?", "How may I cease/sustain this undesirable/desirable experience?" are examples of introspection.[40] It is important to note that introspection is only an inner observation; verbalizing the contents, especially outloud, is considered an entirely different process.[41]

This state of mind is effective at facilitating therapeutic self-improvement and positive personal growth. Contrary to early psychological assumptions, introspection appears to be an ability that can be honed; humans do not have automatic or unbiased access to experience.[37][38] Increasing introspection often results in insightful resolutions to the present situation, future possibilities, insecurities, and goals coinciding with personal acceptance of insecurities, fears, hopes, struggles, and traumas.

Increased introspection is likely the result of a combination of an appropriate setting in conjunction with other coinciding effects such as analysis enhancement, mindfulness,[37] and personal bias suppression. It is most commonly induced during meditation[38] or under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics[42] and dissociatives.[36][43][44] However, it can also occur in a less consistent form under the influence of entactogens.

Outrospection

Analysis enhancement is defined as a perceived improvement of a person's overall ability to logically process information[45][46][47] or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios. This effect can lead to a deep state of contemplation which often results in an abundance of new and insightful ideas. It can give the person a perceived ability to better analyze concepts and problems in a manner which allows them to reach new conclusions, perspectives, and solutions which would have been otherwise difficult to conceive of.

Although this effect will often result in deep states of introspection, in other cases it can produce states which are not introspective but instead result in a deep analysis of the exterior world, both taken as a whole and as the things which comprise it. This can result in a perceived abundance of insightful ideas and conclusions with powerful themes pertaining to what is often described as "the bigger picture". These ideas generally involve (but are not limited to) insight into philosophy, science, spirituality, society, culture, universal progress, humanity, loved ones, the finite nature of our lives, history, the present moment, and future possibilities.

Cognitive performance is undeniably linked to personality,[48] and it has been repeatedly shown that psychedelics alter a user's personality for the long term. Experienced psychedelics users score significantly better than controls on several psychometric measures.[49]

Analysis enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, conceptual thinking, and thought connectivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, nicotine, and caffeine.[45][47] However, it can also occur in a more powerful although less consistent form under the influence of psychedelics such as certain LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[49]

Rejuvenation

Rejuvenation can be described as feelings of mild to extreme cognitive refreshment which are felt during the afterglow of certain compounds. The symptoms of rejuvenation often include a sustained sense of heightened mental clarity, increased emotional stability, increased calmness, mindfulness, increased motivation, personal bias suppression, increased focus and decreased depression. At its highest level, feelings of rejuvenation can become so intense that they manifest as the profound and overwhelming sensation of being "reborn" anew. This mindstate can potentially last anywhere from several hours to several months after the substance has worn off.

Rejuvination is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Deja-Vu

Déjà Vu (or Deja Vu) is defined as as any sudden inappropriate impression of familiarity of a present experience with an undefined past.[50][51][52][53] Its two critical components are an intense feeling of familiarity, and a certainty that the current moment is novel.[54] This term is a common phrase from the French language which translates literally into “already seen”. It is a well-documented phenomenon that can commonly occur throughout both sober living and under the influence of hallucinogens.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, many compounds are commonly capable of inducing spontaneous and often prolonged states of mild to intense sensations of déjà vu. This can provide one with an overwhelming sense that they have “been here before”. The sensation is also often accompanied by a feeling of familiarity with the current location or setting, the current physical actions being performed, the situation as a whole, or the effects of the substance itself.

This effect is often triggered despite the fact that during the experience of it, the person can be rationally aware that the circumstances of the “previous” experience (when, where, and how the earlier experience occurred) are uncertain or believed to be impossible.

Déjà vu is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as olfactory hallucinations and derealization.[55] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[56] such as psychedelics,[57] cannabinoids,[58] and dissociatives.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness can be described as a psychological concept which is well established within the scientific literature and commonly discussed in association with meditation.[59][60]

It is often broken down into two separate subcomponents which comprise this effect: The first of these components involves the self-regulation of attention so that its focus is completely directed towards immediate experience, thereby quietening one's internal narrative and allowing for increased recognition of external and mental events within the present moment.[61][62] The second of these components involves adopting a particular orientation toward one’s experiences in the present moment that is characterized by a lack of judgement, curiosity, openness, and acceptance.[63]

Within meditation, this state of mind is deliberately practised and maintained via the conscious and manual redirection of one's awareness towards a singular point of focus for extended periods of time. However, within the context of psychoactive substance usage, this state is often spontaneously induced without any conscious effort or the need of any prior knowledge regarding meditative techniques.

Mindfulness is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety suppression and focus intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids. However, it can also occur on entactogens, certain nootropics such as l-theanine, and during simultaneous doses of benzodiazepines and stimulants.

Multiple thought streams

Multiple thought streams is defined as a state of mind in which a person has more than one internal narrative or stream of consciousness simultaneously occurring within their head. This can result in any number of independent thought streams occurring at the same time, each of which are often controllable in a similar manner to that of one's everyday thought stream.

These multiple coinciding thought streams can be experienced simultaneously in a manner which is evenly distributed and does not prioritize the awareness of any particular thought stream over an other. However, they can also be experienced in a manner which feels as if it brings awareness of a particular thought stream to the foreground while the others continue processing information in the background. This form of multiple thought streams typically swaps between specific trains of thought at seemingly random intervals.

The experience of this effect can sometimes allow one to analyze many different ideas simultaneously and can be a source of great insight. However, it will usually overwhelm the person with an abundance of information that becomes difficult or impossible to fully process at a normal speed.

Multiple thought streams are often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression and thought disorganization. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Suppression of personal bias

Cognitive effects: Suppression of personal bias

Feelings of predeterminism

Perception of predeterminism can be described as the sensation that all physical and mental processes are the result of prior causes, that every event and choice is an inevitable outcome that could not have happened differently, and that all of reality is a complex causal chain that can be traced back to the beginning of time. This is accompanied by the absence of the feeling that a person's decision-making processes and general cognitive faculties inherently possess "free will”. This sudden change in perspective causes the person to feel as if their personal choices, physical actions, and individual personality traits have always been completely predetermined by prior causes and are, therefore, outside of their conscious control.

During this state, a person begins to feel as if their decisions arise from a complex set of internally stored, pre-programmed, and completely autonomous, instant electrochemical responses to perceived sensory input. These sensations are often interpreted as somehow disproving the concept of free will, as the experience of this effect feels as if it is fundamentally incompatible with the notion of being self-determined. This state can also lead a person to the conclusion that their very identity and selfhood are the cumulative results of their biology and past experiences.

Once the effect begins to wear off, a person will often return to their everyday feelings of freedom and independence. Despite this, however, they will often retain realizations regarding what is often interpreted as a profound insight into the apparent illusory nature of free will.

Perception of predeterminism is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as ego dissolution and physical autonomy. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Conceptual thinking

Conceptual thinking is defined as an alteration to the nature and content of one's internal thought stream. This alteration predisposes a user to think thoughts which are no longer primarily comprised of words and linear sentence structures. Instead, thoughts become equally comprised of what is perceived to be incredibly detailed renditions of the innately understandable and internally stored concepts for which no words exist. Thoughts cease to be spoken by an internal narrator and are instead “felt” and intuitively understood.

For example, if a person was to think of an idea such as a "chair" during this state, one would not hear the word as part of an internal thought stream, but would feel the internally stored, pre-linguistic and innately understandable data which comprises the specific concept labelled within one's memory as a "chair". These conceptual thoughts are felt in a comprehensive level of detail that feels as if it is unparalleled within the primarily linguistic thought structure of everyday life. This is sometimes interpreted by those who undergo it as some "higher level of understanding".

During this experience, conceptual thinking can cause one to feel not just the entirety of a concept's attributed data, but also how a given concept relates to and depends upon other known concepts. This can result in the perception that the person can better comprehend the complex interplay between the idea that is being contemplated and how it relates to other ideas.

Conceptual thinking is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression and analysis enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Direct communication with the subconscious

Autonomous voice communication (also known as auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs))[64] is defined as the experience of being able to hear and converse with a disembodied and audible voice of unknown origin which seemingly resides within one's own head.[65][66][67][68] This voice is often capable of high levels of complex and detailed speech which are typically on par with the intelligence and vocabulary of ones own conversational abilities.

As a whole, the effect itself can be broken down into 5 distinct levels of progressive intensity, each of which are described below:

- A sensed presence of the other - The distinctive feeling that another form of consciousness is internally present alongside that of one's usual sense of self. This sensation is often referred to within the scientific literature as a "sense of presence".[66][69][70][71]

- Mutually generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are partially generated by one's own thought stream and in equal measure by that of a separate thought stream.[72]

- Separately generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are generated by an entirely distinct and separate thought stream that resides within one's head.[64][66][72]

- Separately generated audible internal responses - Internally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice within one's head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to one's own spoken voice.[65][72]

- Separately generated audible external responses - Externally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice which sounds as if it is coming from outside one's own head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to the person's own spoken voice.[65][66][72]

The speaker behind this voice is commonly interpreted by those who experience it to be the voice of their own subconscious, the psychoactive substance itself, a specific autonomous entity, or even supernatural concepts such as god, spirits, souls, and ancestors.

At higher levels, the conversational style of that which is discussed between both the voice and its host can be described as essentially identical in terms of its coherency and linguistic intelligibility as that of any other everyday interaction between the self and another human being of any age with which one might engage in conversation with. Higher levels may also manifest itself in multiple voices or even an ambiguous collection of voices such as a crowd.[66]

However, there are some subtle but identifiable differences between this experience and that of normal everyday conversations. These stem from the fact that one's specific set of knowledge, memories and experiences are identical to that of the voice which is being communicated with.[66][68] This results in conversations in which both participants often share an identical vocabulary down to the very use of their colloquial slang and subtle mannerisms. As a result of this, no matter how in-depth and detailed the discussion becomes, no entirely new information is ever exchanged between the two communicators. Instead, the discussion focuses primarily on building upon old ideas and discussing new opinions or perspectives regarding the previously established content of one's life.

Autonomous voice communication is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as delusions, autonomous entities, auditory hallucinations, and psychosis in a manner which can sometimes lead the person into believing the voices' statements unquestionably in a delusional manner. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. However, it may also occur during the offset of prolonged stimulant binges and less consistently under the influence of heavy dosages of cannabinoids.

Ego suppression, loss and death

Cognitive effects: Ego suppression, loss and death

Personality regression

Personality regression is a mental state in which one suddenly adopts an identical or similar personality, thought structure, mannerisms and behaviours to that of their past self from a younger age.[73] During this state, the person will often believe that they are literally a child again and begin outwardly exhibiting behaviours which are consistent to this belief. These behaviours can include talking in a childlike manner, engaging in childish activities, and temporarily requiring another person to act as a caregiver or guardian. There are also anecdotal reports of people speaking in languages which they have not used for many years under the influence of this effect.[74]

Personality regression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, memory suppression, and ego dissolution. It is a relatively rare effect that is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, most notably Ayahuasca, LSD and Ibogaine in particular as well as certain dissociatives. However, it can also occur for people during times of stress,[73] as a response to childhood trauma, as a symptom of borderline personality disorder,[75] or as a regularly reoccuring facet of certain peoples lives that is not necessarily associated with any psychological problems.

Thought loops

A thought loop is defined as the experience of becoming trapped within a chain of thoughts, actions and emotions which repeats itself over and over again in a cyclic loop. These loops usually range from anywhere between 5 seconds and 2 minutes in length. However, some users have reported them to be up to a few hours in length. It can be extremely disorientating to undergo this effect and it often triggers states of progressive anxiety within people who may be unfamiliar with the experience. The most effective way to end a cycle of thought loops is to simply sit down and try to let go.

This state of mind is most likely to occur during states of memory suppression in which there is a partial or complete failure of the person's short-term memory. This may suggest that thought loops are the result of cognitive processes becoming unable to sustain themselves for appropriate lengths of time due to a lapse in short-term memory, resulting in the thought process attempting to restart from the beginning only to fall short once again in a perpetual cycle.

Thought loops are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[76] such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of stimulants and benzodiazepines.

Feelings of interdependent opposites

Perception of interdependent opposites can be described as the experience of a powerful subjective feeling that reality is based upon a binary system in which the existence of fundamentally important concepts or situations logically arise from and depend upon the co-existence of their opposite. This perception is not just understood at a cognitive level, but manifests as intuitive sensations which are felt rather than thought by the person.

This experience is usually interpreted as providing a deep insight into the fundamental nature of reality. For example, concepts such as existence and non-existence, life and death, up and down, self and other, light and dark, good and bad, big and small, pleasure and suffering, yes and no, internal and external, hot and cold, young and old, etc are felt to exist as harmonious forces which necessarily contrast their opposite force in a state of equilibrium.

Perception of interdependent opposites is often accompanied by other coinciding transpersonal effects such as ego dissolution, unity and interconnectedness, and perception of eternalism. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Delusions

A delusion is a false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly held despite what almost everyone else believes and despite what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the contrary. The belief is not ordinarily accepted by other members of the person's culture or subculture (i.e., it is not an article of religious faith). When a false belief involves a value judgement, it is regarded as a delusion only when the judgement is so extreme as to defy credibility. Delusional conviction can sometimes be inferred from an overvalued idea (in which case the individual has an unreasonable belief or idea but does not hold it as firmly as is the case with a delusion).[77][78][79]

This article focuses primarily on the types of delusion that are commonly induced by hallucinogens or other psychoactive substances, as opposed to the various categories that are listed within the DSM as occurring within people who suffer from psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Although there are common themes between these two causes of delusion, the underlying circumstances are distinct enough that they are seemingly very different in their themes, behaviour, and frequency of occurrence.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, delusions can usually be broken out of when overwhelming evidence is provided to the contrary or when the person has sobered up enough to logically analyse the situation. It is exceedingly rare for hallucinogen induced delusions to persist into sobriety.

It is also worth noting that delusions can often spread between individuals in group settings.[80] For example, if one person makes a verbal statement regarding a delusional belief they are currently holding while in the presence of other similarly intoxicated people, these other people may also begin to hold the same delusion. This can result in shared hallucinations and a general reinforcement of the level of conviction in which they are each holding the delusional belief.

Delusions are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, deliriants, and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, stimulant psychosis, and sleep deprivation. They are most likely to occur during states of memory suppression and share common themes and elements with clinical schizophrenia.

States of unity and interconnectedness

Unity and interconnectedness can be described as the experience of one's sense of self becoming temporarily changed to feel as if it is constituted by a wider array of concepts than that which it previously did. For example, while a person may usually feel that they are exclusively their “ego” or a combination of their “ego” and physical body, during this state their sense of identity can change to also include the external environment or an object they are interacting with. This results in intense and inextricable feelings of unity or interconnectedness between oneself and varying arrays of previously "external" systems.

It is worth noting that many people who undergo this experience consistently interpret it as the removal of a deeply embedded illusion, the destruction of which is often described as some sort of profound “awakening” or “enlightenment.” However, it is important to understand that these conclusions and feelings should not necessarily be accepted at face value as inherently true.

Unity and interconnectedness most commonly occurs under the influence of psychedelic and dissociative compounds such as LSD, DMT, ayahuasca, mescaline, and ketamine. However it can also occur during well-practiced meditation, deep states of contemplation, and intense focus.

There are a total of 5 distinct levels of identity which a person can experience during this state. These various altered states of unity have been arranged into a leveling system that orders its different states from least to the most number of concepts that one's identity is currently attributed to. These levels are described below:

1. Unity between specific "external" systems

At the lowest level, this effect can be described as a perceived sense of unity between two or more systems within the external environment which in everyday life are usually perceived as separate from each other. This is the least complex level of unity, as it is the only level of interconnectedness in which the subjective experience of unity does not involve a state of interconnectedness between the self and the external.

There are an endless number of ways in which this level can manifest, but common examples of the experience often include:

- A sense of unity between specific living things such as animals or plants and their surrounding ecosystems.

- A sense of unity between other human beings and the objects they are currently interacting with.

- A sense of unity between any number of currently perceivable inanimate objects.

- A sense of unity between humanity and nature.

- A sense of unity between literally any combination of perceivable external systems and concepts.

2. Unity between the self and specific "external" systems

At this level, unity can be described as feeling as if one's identity is attributed to (in addition to the body and/or brain) specific external systems or concepts within the immediate environment, particularly those that would usually be considered as intrinsically separate from one's own being.

The experience itself is often described as a loss of perceived boundaries between a person’s identity and the specific physical systems or concepts within the perceivable external environment which are currently the subject of a person's attention. This creates a sensation of becoming inextricably "connected to", "one with", "the same as", or "unified" with whatever the perceived external system happens to be.

There are an endless number of ways in which this level can manifest itself, but common examples of the experience often include:

- Becoming unified with and identifying with a specific object one is interacting with.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with another person or multiple people, particularly common if engaging in sexual or romantic activities.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with the entirety of one's own physical body.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with large crowds of people, particularly common at raves and music festivals.

- Becoming unified with and identifying with the external environment, but not the people within it.

3. Unity between the self and all perceivable "external" systems

At this level, unity can be described as feeling as if one's identity is attributed to the entirety of their immediately perceivable external environment due to a loss of perceived boundaries between the previously separate systems.

The effect creates a sensation in the person that they have become "one with their surroundings.” This is felt to be the result of a person’s sense of self becoming attributed to not just primarily the internal narrative of the ego, but in equal measure to the body itself and everything around it which it is physically perceiving through the senses. It creates the compelling perspective that one is the external environment experiencing itself through a specific point within it, namely the physical sensory perceptions of the body that one's consciousness is currently residing in.

It is at this point that a key component of the high-level unity experience becomes an extremely noticeable factor. Once a person's sense of self has become attributed to the entirety of their surroundings, this new perspective completely changes how it feels to physically interact with what was previously felt to be an external environment. For example, when one is not in this state and is interacting with a physical object, it typically feels as though one is a central agent acting on the separate world around them. However, while undergoing a state of unity with the currently perceivable environment, interacting with an external object consistently feels as if the whole unified system is autonomously acting on itself with no central, separate agent operating the process of interaction. Instead, the process suddenly feels as if it has become completely decentralized and holistic, as the environment begins to autonomously and harmoniously respond to itself in a predetermined manner to perform the interaction carried out by the individual.

4. Unity between the self and all known "external" systems

At the highest level, this effect can be described as feeling as if one's identity is simultaneously attributed to the entirety of the immediately perceivable external environment and all known concepts that exist outside of it. These known concepts typically include all of humanity, nature, and the universe as it presently stands in its complete entirety. This feeling is commonly interpreted by people as "becoming one with the universe".

When experienced, the effect creates the sudden perspective that one is not a separate agent approaching an external reality, but is instead the entire universe as a whole experiencing itself, exploring itself, and performing actions upon itself through the specific point in space and time which this particular body and conscious perception happens to currently reside within. People who undergo this experience consistently interpret it as the removal of a deeply embedded illusion, with the revelation often described as some sort of profound “awakening” or “enlightenment.”

Although they are not necessarily literal truths about reality, at this point, many commonly reported conclusions of a religious and metaphysical nature often begin to manifest themselves as profound realizations. These are described and listed below:

- The sudden and total acceptance of death as a fundamental complement of life. Death is no longer felt to be the destruction of oneself, but simply the end of this specific point of a greater whole, which has always existed and will continue to exist and live on through everything else in which it resides. Therefore, the death of a small part of the whole is seen as an inevitable, and not worthy of grief or any emotional attachment, but simply a fact of reality.

- The subjective perspective that one's preconceived notions of "god" or deities can be felt as identical to the nature of existence and the totality of its contents, including oneself. This typically entails the intuition that if the universe contains all possible power (omnipotence), all possible knowledge (omniscience), is self-creating, and self-sustaining then on either a semantic or literal level the universe and its contents could also be viewed as a god.

- The subjective perspective that one, by nature of being the universe, is personally responsible for the design, planning, and implementation of every single specific detail and plot element of one's personal life, the history of humanity, and the entirety of the universe. This naturally includes personal responsibility for all humanity's sufferings and flaws but also includes its acts of love and achievements.

See also

- Psychedelics

- Visual effects - Psychedelics

- Auditory effects - Psychedelics

- Physical effects - Psychedelics

- Multi-Sensory effects - Psychedelics

- Dissociatives

- Deliriants

- Hallucinogens

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Gasser, Peter; Kirchner, Katharina; Passie, Torsten (2014). "LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: A qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 29 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1177/0269881114555249. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kaelen, M.; Barrett, F. S.; Roseman, L.; Lorenz, R.; Family, N.; Bolstridge, M.; Curran, H. V.; Feilding, A.; Nutt, D. J.; Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2015). "LSD enhances the emotional response to music". Psychopharmacology. 232 (19): 3607–3614. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-4014-y. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hartogsohn, Ido (2018). "The Meaning-Enhancing Properties of Psychedelics and Their Mediator Role in Psychedelic Therapy, Spirituality, and Creativity". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00129. ISSN 1662-453X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Swanson, Link R. (2018). "Unifying Theories of Psychedelic Drug Effects". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00172. ISSN 1663-9812.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Miller, Melissa A.; Bershad, Anya K.; de Wit, Harriet (2015). "Drug effects on responses to emotional facial expressions". Behavioural Pharmacology. 26 (6): 571–579. doi:10.1097/FBP.0000000000000164. ISSN 0955-8810.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Belser, Alexander B.; Agin-Liebes, Gabrielle; Swift, T. Cody; Terrana, Sara; Devenot, Neşe; Friedman, Harris L.; Guss, Jeffrey; Bossis, Anthony; Ross, Stephen (2017). "Patient Experiences of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 57 (4): 354–388. doi:10.1177/0022167817706884. ISSN 0022-1678.

- ↑ Kamboj, Sunjeev K.; Joye, Alyssa; Bisby, James A.; Das, Ravi K.; Platt, Bradley; Curran, H. Valerie (2012). "Processing of facial affect in social drinkers: a dose–response study of alcohol using dynamic emotion expressions". Psychopharmacology. 227 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2940-5. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ Philippot, Pierre; Kornreich, Charles; Blairy, Sylvie; Baert, Iseult; Dulk, Anne Den; Bon, Olivier Le; Streel, Emmanuel; Hess, Ursula; Pelc, Isy; Verbanck, Paul (1999). "Alcoholics'Deficits in the Decoding of Emotional Facial Expression". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 23 (6): 1031–1038. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04221.x. ISSN 0145-6008.

- ↑ Wardle, Margaret C.; Garner, Matthew J.; Munafò, Marcus R.; de Wit, Harriet (2012). "Amphetamine as a social drug: effects of d-amphetamine on social processing and behavior". Psychopharmacology. 223 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2708-y. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Piguet, Camille; Dayer, Alexandre; Kosel, Markus; Desseilles, Martin; Vuilleumier, Patrik; Bertschy, Gilles (2010). "Phenomenology of racing and crowded thoughts in mood disorders: A theoretical reappraisal". Journal of Affective Disorders. 121 (3): 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.006. ISSN 0165-0327.

- ↑ Pronin, Emily; Jacobs, Elana; Wegner, Daniel M. (2008). "Psychological effects of thought acceleration". Emotion. 8 (5): 597–612. doi:10.1037/a0013268. ISSN 1931-1516.

- ↑ Yang, Kaite; Friedman-Wheeler, Dara G.; Pronin, Emily (2014). "Thought Acceleration Boosts Positive Mood Among Individuals with Minimal to Moderate Depressive Symptoms". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 38 (3): 261–269. doi:10.1007/s10608-014-9597-9. ISSN 0147-5916.

- ↑ Pronin, Emily; Jacobs, Elana (2008). "Thought Speed, Mood, and the Experience of Mental Motion". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 3 (6): 461–485. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00091.x. ISSN 1745-6916.

- ↑ Carhart-Harris, Robin L.; Leech, Robert; Hellyer, Peter J.; Shanahan, Murray; Feilding, Amanda; Tagliazucchi, Enzo; Chialvo, Dante R.; Nutt, David (2014). "The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020. ISSN 1662-5161.

- ↑ Tagliazucchi, Enzo; Carhart-Harris, Robin; Leech, Robert; Nutt, David; Chialvo, Dante R. (2014). "Enhanced repertoire of brain dynamical states during the psychedelic experience". Human Brain Mapping. 35 (11): 5442–5456. doi:10.1002/hbm.22562. ISSN 1065-9471.

- ↑ Hu, Dewen; Palhano-Fontes, Fernanda; Andrade, Katia C.; Tofoli, Luis F.; Santos, Antonio C.; Crippa, Jose Alexandre S.; Hallak, Jaime E. C.; Ribeiro, Sidarta; de Araujo, Draulio B. (2015). "The Psychedelic State Induced by Ayahuasca Modulates the Activity and Connectivity of the Default Mode Network". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0118143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118143. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Hunt, Harry T. (1976). "A Test of the Psychedelic Model of Altered States of Consciousness". Archives of General Psychiatry. 33 (7): 867. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770070097012. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ Bonner, Edward T.; Friedman, Harris L. (2011). "A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: An interpretative phenomenological analysis". The Humanistic Psychologist. 39 (3): 222–235. doi:10.1080/08873267.2011.593372. ISSN 1547-3333.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Griffiths, Roland R; Johnson, Matthew W; Richards, William A; Richards, Brian D; Jesse, Robert; MacLean, Katherine A; Barrett, Frederick S; Cosimano, Mary P; Klinedinst, Maggie A (2017). "Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 32 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1177/0269881117731279. ISSN 0269-8811.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Das, Saibal; Barnwal, Preeti; Ramasamy, Anand; Sen, Sumalya; Mondal, Somnath (2016). "Lysergic acid diethylamide: a drug of 'use'?". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 6 (3): 214–228. doi:10.1177/2045125316640440. ISSN 2045-1253.

- ↑ Bowers, Malcolm B. (1966). ""Psychedelic" Experiences in Acute Psychoses". Archives of General Psychiatry. 15 (3): 240. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1966.01730150016003. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ N. Stanciu, C., M. Penders, T. (1 June 2016). "Hallucinogen Persistent Perception Disorder Induced by New Psychoactive Substituted Phenethylamines; A Review with Illustrative Case". Current Psychiatry Reviews. 12 (2): 221–223.

- ↑ Nichols, D. E. (2016). "Psychedelics". Pharmacological Reviews. 68 (2): 264–355. doi:10.1124/pr.115.011478. ISSN 1521-0081.

- ↑ Pink-Hashkes, S., Rooij, I. J. E. I. van, Kwisthout, J. H. P. (2017). "Perception is in the details: A predictive coding account of the psychedelic phenomenon". London, UK : Cognitive Science Society.

- ↑ Hill, R. M.; Fischer, R.; Warshay, Diana (1969). "Effects of excitatory and tranquilizing drugs on visual perception. spatial distortion thresholds". Experientia. 25 (2): 171–172. doi:10.1007/BF01899105. ISSN 0014-4754.

- ↑ Fischer, R. (1971). "A Cartography of the Ecstatic and Meditative States". Science. 174 (4012): 897–904. doi:10.1126/science.174.4012.897. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Buckley, P. (1981). "Mystical Experience and Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 7 (3): 516–521. doi:10.1093/schbul/7.3.516. ISSN 0586-7614.

- ↑ Schroll, M. A. (2013). "From ecopsychology to transpersonal ecosophy: Shamanism, psychedelics and transpersonal psychology" (PDF). European Journal of Ecopsychology. 4: 116–144.

- ↑ Riley, Sarah C.E.; Blackman, Graham (2009). "Between Prohibitions: Patterns and Meanings of Magic Mushroom Use in the UK". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1080/10826080701772363. ISSN 1082-6084.

- ↑ Nikolova, I.; Danchev, N. (2014). "Piperazine Based Substances of Abuse: A new Party Pills on Bulgarian Drug Market". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 22 (2): 652–655. doi:10.1080/13102818.2008.10817529. ISSN 1310-2818.

- ↑ Yeap, C. W., Bian, C. K., Abdullah, A. F. L. (2010). "A Review on Benzylpiperazine and Trifluoromethylphenypiperazine: Origins, Effects, Prevalence and Legal Status". Health and the Environment Journal. 1 (2): 38–50.

- ↑ Griffith, John D.; Nutt, John G.; Jasinski, Donald R. (1975). "A comparison of fenfluramine and amphetamine in man". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 18 (5part1): 563–570. doi:10.1002/cpt1975185part1563. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ↑ Corazza, Ornella; Assi, Sulaf; Schifano, Fabrizio (2013). "From "Special K" to "Special M": The Evolution of the Recreational Use of Ketamine and Methoxetamine". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 19 (6): 454–460. doi:10.1111/cns.12063. ISSN 1755-5930.

- ↑ APA Dictionary of Psychology, retrieved 15 October 2022

- ↑ Schwitzgebel, E. (2019). "The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy". In Zalta, E. N. Introspection (Winter 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Palhano-Fontes, F., Andrade, K. C., Tofoli, L. F., Santos, A. C., Crippa, J. A. S., Hallak, J. E. C., Ribeiro, S., Araujo, D. B. de (18 February 2015). Hu, D., ed. "The Psychedelic State Induced by Ayahuasca Modulates the Activity and Connectivity of the Default Mode Network". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0118143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118143. ISSN 1932-6203. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Frank, P., Sundermann, A., Fischer, D. (4 October 2019). "How mindfulness training cultivates introspection and competence development for sustainable consumption". International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education. 20 (6): 1002–1021. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-12-2018-0239. ISSN 1467-6370. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Fox, K. C. R., Zakarauskas, P., Dixon, M., Ellamil, M., Thompson, E., Christoff, K. (25 September 2012). Martinez, L. M., ed. "Meditation Experience Predicts Introspective Accuracy". PLoS ONE. 7 (9): e45370. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045370. ISSN 1932-6203. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ↑ Overgaard, M., Mogensen, J. (March 2017). "An integrative view on consciousness and introspection". Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 8 (1): 129–141. doi:10.1007/s13164-016-0303-6. ISSN 1878-5158. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ↑ Xue, H., Desmet, P. M. A. (July 2019). "Researcher introspection for experience-driven design research". Design Studies. 63: 37–64. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2019.03.001. ISSN 0142-694X. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ↑ Ericsson, K. A., Fox, M. C. (2011). "Thinking aloud is not a form of introspection but a qualitatively different methodology: Reply to Schooler (2011)". Psychological Bulletin. 137 (2): 351–354. doi:10.1037/a0022388. ISSN 1939-1455. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ↑ Riga, M. S., Soria, G., Tudela, R., Artigas, F., Celada, P. (August 2014). "The natural hallucinogen 5-MeO-DMT, component of Ayahuasca, disrupts cortical function in rats: reversal by antipsychotic drugs". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (08): 1269–1282. doi:10.1017/S1461145714000261. ISSN 1461-1457. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ Barker, S. A. (6 August 2018). "N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, Present, and Future Research to Determine Its Role and Function". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 536. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00536. ISSN 1662-453X. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ Santos, R. G. dos, Osório, F. L., Crippa, J. A. S., Hallak, J. E. C. (December 2016). "Classical hallucinogens and neuroimaging: A systematic review of human studies". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 71: 715–728. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.10.026. ISSN 0149-7634. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Fillmore, Mark T.; Kelly, Thomas H.; Martin, Catherine A. (2005). "Effects of d-amphetamine in human models of information processing and inhibitory control". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 77 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.013. ISSN 0376-8716.

- ↑ Bättig, K.; Buzzi, R. (1986). "Effect of Coffee on the Speed of Subject-Paced Information Processing". Neuropsychobiology. 16 (2-3): 126–130. doi:10.1159/000118312. ISSN 0302-282X.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Warburton, David; Bersellini, Elisabetta; Sweeney, Eve (2001). "An evaluation of a caffeinated taurine drink on mood, memory and information processing in healthy volunteers without caffeine abstinence". Psychopharmacology. 158 (3): 322–328. doi:10.1007/s002130100884. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ Humphreys, Michael S.; Revelle, William (1984). "Personality, motivation, and performance: A theory of the relationship between individual differences and information processing". Psychological Review. 91 (2): 153–184. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.91.2.153. ISSN 1939-1471.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Bouso, José Carlos; Palhano-Fontes, Fernanda; Rodríguez-Fornells, Antoni; Ribeiro, Sidarta; Sanches, Rafael; Crippa, José Alexandre S.; Hallak, Jaime E.C.; de Araujo, Draulio B.; Riba, Jordi (2015). "Long-term use of psychedelic drugs is associated with differences in brain structure and personality in humans". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (4): 483–492. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.01.008. ISSN 0924-977X.

- ↑ O’Connor, A. R., Wells, C., Moulin, C. J. A. (9 August 2021). "Déjà vu and other dissociative states in memory". Memory. 29 (7): 835–842. doi:10.1080/09658211.2021.1911197. ISSN 0965-8211. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Funkhouser, A. T., Schredl, M. (2010). "The frequency of déjà vu (déjà rêve) and the effects of age, dream recall frequency and personality factors". doi:10.11588/IJODR.2010.1.473. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Brown, A. S. (2003). "A review of the déjà vu experience". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (3): 394–413. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.394. ISSN 1939-1455.

- ↑ Wild, E. (January 2005). "Deja vu in neurology". Journal of Neurology. 252 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s00415-005-0677-3. ISSN 0340-5354. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ O’Connor, A. R., Moulin, C. J. A. (June 2010). "Recognition Without Identification, Erroneous Familiarity, and Déjà Vu". Current Psychiatry Reports. 12 (3): 165–173. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0119-5. ISSN 1523-3812.

- ↑ Warren-Gash, C., Zeman, A. (1 February 2014). "Is there anything distinctive about epileptic deja vu?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 85 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-303520. ISSN 0022-3050. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Doss, M. K., Samaha, J., Barrett, F. S., Griffiths, R. R., Wit, H. de, Gallo, D. A., Koen, J. D. (2022), Unique Effects of Sedatives, Dissociatives, Psychedelics, Stimulants, and Cannabinoids on Episodic Memory: A Review and Reanalysis of Acute Drug Effects on Recollection, Familiarity, and Metamemory, Neuroscience, retrieved 16 June 2022

- ↑ Luke, D. P. (2008). "Psychedelic substances and paranormal phenomena: a review of the research". Journal of Parapsychology. 72: 77–107. ISSN 0022-3387. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Basu, D., Malhotra, A., Bhagat, A., Varma, V. K. (1999). "Cannabis Psychosis and Acute Schizophrenia". European Addiction Research. 5 (2): 71–73. doi:10.1159/000018968. ISSN 1022-6877. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Slagter, H. A., Davidson, R. J., Lutz, A. (2011). "Mental Training as a Tool in the Neuroscientific Study of Brain and Cognitive Plasticity". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 5. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00017. ISSN 1662-5161.

- ↑ Pagnini, F., Philips, D. (April 2015). "Being mindful about mindfulness". The Lancet Psychiatry. 2 (4): 288–289. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00041-3. ISSN 2215-0366.

- ↑ Baer, R. A. (2003). "Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 10 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. ISSN 1468-2850.

- ↑ Creswell, J. D. (3 January 2017). "Mindfulness Interventions". Annual Review of Psychology. 68 (1): 491–516. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. ISSN 0066-4308.

- ↑ Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., Devins, G. (2004). "Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 11 (3): 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077. ISSN 1468-2850.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Toh, Wei Lin; Castle, David J.; Thomas, Neil; Badcock, Johanna C.; Rossell, Susan L. (2016). "Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) and related psychotic phenomena in mood disorders: analysis of the 2010 Survey of High Impact Psychosis (SHIP) data". Psychiatry Research. 243: 238–245. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.035. ISSN 0165-1781.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Moseley, Peter; Fernyhough, Charles; Ellison, Amanda (2013). "Auditory verbal hallucinations as atypical inner speech monitoring, and the potential of neurostimulation as a treatment option". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 37 (10): 2794–2805. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.10.001. ISSN 0149-7634.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 66.5 Woods, Angela; Jones, Nev; Alderson-Day, Ben; Callard, Felicity; Fernyhough, Charles (2015). "Experiences of hearing voices: analysis of a novel phenomenological survey". The Lancet Psychiatry. 2 (4): 323–331. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00006-1. ISSN 2215-0366.

- ↑ Romme, M. A. J.; Honig, A.; Noorthoorn, E. O.; Escher, A. D. M. A. C. (2018). "Coping with Hearing Voices: An Emancipatory Approach". British Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (01): 99–103. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.1.99. ISSN 0007-1250.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Corstens, Dirk; Longden, Eleanor; McCarthy-Jones, Simon; Waddingham, Rachel; Thomas, Neil (2014). "Emerging Perspectives From the Hearing Voices Movement: Implications for Research and Practice". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 40 (Suppl_4): S285–S294. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu007. ISSN 1745-1701.

- ↑ Fenelon, G.; Soulas, T.; de Langavant, L. C.; Trinkler, I.; Bachoud-Levi, A.-C. (2011). "Feeling of presence in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 82 (11): 1219–1224. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.234799. ISSN 0022-3050.

- ↑ Hayes, Jacqueline; Leudar, Ivan (2016). "Experiences of continued presence: On the practical consequences of 'hallucinations' in bereavement". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 89 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1111/papt.12067. ISSN 1476-0835.

- ↑ SherMer, M. (2010). The Sensed-Presence Effect. Scientific American, 302(4), 34. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-sensed-presence-effect/

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Looijestijn, Jasper; Diederen, Kelly M.J.; Goekoop, Rutger; Sommer, Iris E.C.; Daalman, Kirstin; Kahn, René S.; Hoek, Hans W.; Blom, Jan Dirk (2013). "The auditory dorsal stream plays a crucial role in projecting hallucinated voices into external space". Schizophrenia Research. 146 (1-3): 314–319. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.004. ISSN 0920-9964.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Lokko, H. N., Stern, T. A. (14 May 2015). "Regression: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 17 (3): 27221. doi:10.4088/PCC.14f01761. ISSN 2155-7780.

- ↑ Fromm, E. (April 1970). "Age regression with unexpected reappearance of a repressed c3ildhood language". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 18 (2): 79–88. doi:10.1080/00207147008415906. ISSN 0020-7144.

- ↑ Viner, J. (January 1983). "An understanding and approach to regression in the borderline patient". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 24 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(83)90049-4. ISSN 0010-440X.

- ↑ Bersani, Francesco Saverio; Corazza, Ornella; Albano, Gabriella; Valeriani, Giuseppe; Santacroce, Rita; Bolzan Mariotti Posocco, Flaminia; Cinosi, Eduardo; Simonato, Pierluigi; Martinotti, Giovanni; Bersani, Giuseppe; Schifano, Fabrizio (2014). "25C-NBOMe: Preliminary Data on Pharmacology, Psychoactive Effects, and Toxicity of a New Potent and Dangerous Hallucinogenic Drug". BioMed Research International. 2014: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/734749. ISSN 2314-6133.

- ↑ "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 819–20. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms.

- ↑ Kiran, C., Chaudhury, S. (1 January 2009). "Understanding delusions". Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 18 (1): 3. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.57851. ISSN 0972-6748.

- ↑ Garety, P. A., Freeman, D. (June 1999). "Cognitive approaches to delusions: A critical review of theories and evidence". British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 38 (2): 113–154. doi:10.1348/014466599162700. ISSN 0144-6657.

- ↑ Arnone, D., Patel, A., Tan, G. M.-Y. (8 August 2006). "The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature". Annals of General Psychiatry. 5 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-5-11. ISSN 1744-859X.