Naturally occurring sources: Difference between revisions

>David Hedlund wording |

>David Hedlund *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallucinogenic_plants_in_Chinese_herbals Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals (Wikipedia)] |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{ | <div data-alert class="alert-box secondary radius" style="background-color: lightyellow; border-color: #8B8000"> | ||

{| | |||

|- | |||

| <div class="icon">[[File:Yellow-warning-sign1.svg|50px|link=]]</div> || <p class="title"><span style="color:#8B8000">'''Research safety before use'''</span></p> | |||

While the following list of plants can be beneficial for various purposes, it's important to note that some of these organisms may contain toxic substances (especially those without articles) in addition, which may pose potential risks if ingested or handled improperly. Before incorporating any of these organisms into your home or garden, we strongly recommend conducting thorough research to understand the specific safety considerations and taking appropriate precautions, especially if you have children or pets. For more information see: Poisonous [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_poisonous_animals animals], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_poisonous_fungus_species fungus], and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_poisonous_plants plants]. And [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_deadly_fungus_species deadly fungus species]. | |||

</p> | |||

|} | |||

</div> | |||

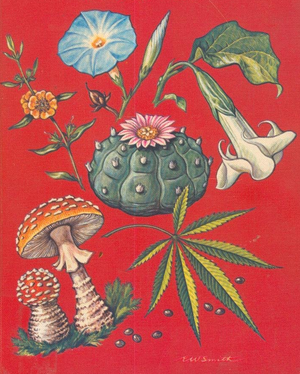

[[File:Biological_sources.png|300px|thumb|right|Artwork from the cover of Hallucinogenic Plants (A Golden Guide)]] | [[File:Biological_sources.png|300px|thumb|right|Artwork from the cover of Hallucinogenic Plants (A Golden Guide)]] | ||

'''Naturally occurring sources''' refers to psychoactive chemicals or their precursors that already exist in nature. This is in contrast to synthetic psychoactive compounds which are artificially produced or designed in laboratories, or [[List of psychoactive substances, and precursor chemicals, produced by GMOs derived from genetically modified organisms|psychoactive substances, and precursor chemicals, produced by GMOs]]. However, these natural chemicals can often be reproduced synthetically as well, though notably they appear in nature or through human cultivation. | '''Naturally occurring sources''' refers to psychoactive chemicals or their precursors that already exist in nature. This is in contrast to synthetic psychoactive compounds which are artificially produced or designed in laboratories, [[List of psychoactive substances derived from artificial fungi biotransformation|psychoactive substances derived from artificial fungi biotransformation]], or [[List of psychoactive substances, and precursor chemicals, produced by GMOs derived from genetically modified organisms|psychoactive substances, and precursor chemicals, produced by GMOs]]. However, these natural chemicals can often be reproduced synthetically as well, though notably they appear in nature or through human cultivation. | ||

==Proposed origins== | ==Proposed origins== | ||

| Line 72: | Line 79: | ||

***[[Anadenanthera peregrina (botany) | ''Anadenanthera peregrina'']] | ***[[Anadenanthera peregrina (botany) | ''Anadenanthera peregrina'']] | ||

***[[Arundo donax (botany) | ''Arundo donax'' (Giant cane)]]<ref name="ErowidArundaInfo2">{{Citation | title=Erowid Arundo donax Vaults : TIHKAL mention of Arundo donax | url=https://www.erowid.org/plants/arundo_donax/arundo_donax_info2.shtml}}</ref> | ***[[Arundo donax (botany) | ''Arundo donax'' (Giant cane)]]<ref name="ErowidArundaInfo2">{{Citation | title=Erowid Arundo donax Vaults : TIHKAL mention of Arundo donax | url=https://www.erowid.org/plants/arundo_donax/arundo_donax_info2.shtml}}</ref> | ||

***''Brosimum acutifolium''<ref name=gaillard>{{cite journal | vauthors = Moretti C, Gaillard Y, Grenand P, Bévalot F, Prévosto JM | title = Identification of 5-hydroxy-tryptamine (bufotenine) in takini (Brosimumacutifolium Huber subsp. acutifolium C.C. Berg, Moraceae), a shamanic potion used in the Guiana Plateau | journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology | volume = 106 | issue = 2 | pages = 198–202 | date = June 2006 | pmid = 16455218 | doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.022 }}</ref> | |||

***''Diplopterys cabrerana'' (Chaliponga) | ***''Diplopterys cabrerana'' (Chaliponga) | ||

***''[[Mucuna pruriens]]''<ref name=chamakura>{{cite journal |author=Chamakura RP |year=1994 |title=Bufotenine—a hallucinogen in ancient snuff powders of South America and a drug of abuse on the streets of New York City |journal=Forensic Sci Rev. |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=2–18}}</ref> | |||

***[[Phalaris (botany) | ''Phalaris'' sp. (Canary grass)]]<ref name="ErowidPhalarisFAQ">{{Citation | title=Erowid Phalaris Vault : FAQ 2.01 | url=https://www.erowid.org/plants/phalaris/phalaris_faq.shtml}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | title=Bufotenin - DMT-Nexus Wiki | url=https://wiki.dmt-nexus.me/Bufotenin#Phalaris_spp}}</ref> | ***[[Phalaris (botany) | ''Phalaris'' sp. (Canary grass)]]<ref name="ErowidPhalarisFAQ">{{Citation | title=Erowid Phalaris Vault : FAQ 2.01 | url=https://www.erowid.org/plants/phalaris/phalaris_faq.shtml}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | title=Bufotenin - DMT-Nexus Wiki | url=https://wiki.dmt-nexus.me/Bufotenin#Phalaris_spp}}</ref> | ||

****[[Phalaris aquatica (botany) | ''Phalaris aquatica'' (Harding grass)]] | ****[[Phalaris aquatica (botany) | ''Phalaris aquatica'' (Harding grass)]] | ||

| Line 199: | Line 208: | ||

<li class="featured list-item"> | <li class="featured list-item"> | ||

<h4 class="media-heading">[[Deliriant]]s</h4> | <h4 class="media-heading">[[Deliriant]]s</h4> | ||

<h5 class="media-heading">Muscarinic Antagonists</h5> | |||

*Platyphylline<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Pomeroy, A. R.)), ((Raper, C.)) | journal=British Journal of Pharmacology | title=Pyrrolizidine alkaloids: actions on muscarinic receptors in the guinea-pig ileum | volume=41 | issue=4 | pages=683–690 | date= April 1971 | url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07076.x | issn=00071188 | doi=10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07076.x}}</ref> | *Platyphylline<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Pomeroy, A. R.)), ((Raper, C.)) | journal=British Journal of Pharmacology | title=Pyrrolizidine alkaloids: actions on muscarinic receptors in the guinea-pig ileum | volume=41 | issue=4 | pages=683–690 | date= April 1971 | url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07076.x | issn=00071188 | doi=10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07076.x}}</ref> | ||

**''Senecio adnatus''<ref name="Senecio">{{Citation | title=Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs - 16th Edition | url=https://www.elsevier.com/books/meylers-side-effects-of-drugs/aronson/978-0-444-53717-1}}</ref> | **''Senecio adnatus''<ref name="Senecio">{{Citation | title=Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs - 16th Edition | url=https://www.elsevier.com/books/meylers-side-effects-of-drugs/aronson/978-0-444-53717-1}}</ref> | ||

| Line 274: | Line 259: | ||

**Latua | **Latua | ||

***''Latua pubiflora'' | ***''Latua pubiflora'' | ||

<h5 class="media-heading">Atypical/Dubious</h5> | |||

*[[Myristicin]] | |||

**[[Anethum graveolens (botany) | ''Anethum graveolens'' (Dill)]] | |||

**[[Apium graveolens (botany) | ''Apium graveolens'' (Celery)]] | |||

**[[Apium nodiflorum (botany) | ''Apium nodiflorum '' (Fool's Watercress)]]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Seneme, E. F.)), ((dos Santos, D. C.)), ((Silva, E. M. R.)), ((Franco, Y. E. M.)), ((Longato, G. B.)) | journal= Molecules | title= Pharmacological and Therapeutic Potential of Myristicin: A Literature Review | volume=26 | issue=19 | date=2021 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8512857/ | doi=10.3390/molecules26195914}}</ref> | |||

**[[Carum carvi (botany) | ''Carum carvi'' (Caraway)]] | |||

**[[Daucus carota (botany) | ''Daucus carota'' (Carrot)]] | |||

**[[Ephedra sinica (botany) | ''Ephedra sinica'' (Ephedra)]] | |||

**[[Foeniculum vulgare (botany) | ''Foeniculum vulgare'' (Fennel)]] | |||

**[[Heracleum anisactis (botany) | ''Heracleum anisactis'' ]]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Seneme, E. F.)), ((dos Santos, D. C.)), ((Silva, E. M. R.)), ((Franco, Y. E. M.)), ((Longato, G. B.)) | journal= Molecules | title= Pharmacological and Therapeutic Potential of Myristicin: A Literature Review | volume=26 | issue=19 | date=2021 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8512857/ | doi=10.3390/molecules26195914}}</ref> | |||

**[[Heracleum pastinacifolium (botany) | ''Heracleum pastinacifolium'']]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Seneme, E. F.)), ((dos Santos, D. C.)), ((Silva, E. M. R.)), ((Franco, Y. E. M.)), ((Longato, G. B.)) | journal= Molecules | title= Pharmacological and Therapeutic Potential of Myristicin: A Literature Review | volume=26 | issue=19 | date=2021 | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8512857/ | doi=10.3390/molecules26195914}}</ref> | |||

**[[Myristica fragrans (botany) | ''Myristica fragrans'' (Nutmeg)]] | |||

**[[Pastinaca sativa (botany) | ''Pastinaca sativa'' (Parsnip)]] | |||

**[[Perilla frutescens (botany) | ''Perilla frutescens'' (Beefsteak mint)]] | |||

**[[Petroselinum crispum (botany) | ''Petroselinum crispum'' (Parsley)]] | |||

*Bisabolol terpenes | |||

**[[Chamomile (botany) | Chamomile]] | |||

*Capsaicinoids | |||

**Capsaicin | |||

***Capsicum genus | |||

*Flavinoids | |||

**[[Chamomile (botany) | Chamomile]] | |||

*Grayanotoxin | |||

**''Rhododendron ponticum'' nectar (mad honey) <ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Jansen, S. A.)), ((Kleerekooper, I.)), ((Hofman, Z. L. M.)), ((Kappen, I. F. P. M.)), ((Stary-Weinzinger, A.)), ((Heyden, M. A. G. van der)) | journal=Cardiovascular Toxicology | title=Grayanotoxin Poisoning: ‘Mad Honey Disease’ and Beyond | volume=12 | issue=3 | pages=208–215 | date= September 2012 | url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12012-012-9162-2 | issn=1530-7905 | doi=10.1007/s12012-012-9162-2}}</ref> | |||

*Ledol | |||

**Labrador tea | |||

***''Rhododendron tomentosum'' | |||

***''Rhododendron groenlandicum'' | |||

***''Rhododendron neoglandulosum'' | |||

</li></ul> | </li></ul> | ||

| Line 619: | Line 633: | ||

***''Backhousia myrtifolia'' | ***''Backhousia myrtifolia'' | ||

***''Canarium luzonicum'' | ***''Canarium luzonicum'' | ||

***''Lagarostrobos franklinii''<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Deans, B.J.)),((De Salas. J)), ((Smith, J.A)),((Bissember, A.C)) | journal= Australian Journal of Chemistry |title= Natural Products Isolated from Endemic Tasmanian | |||

Vascular Plants | volume= 71 | pages= 756-767 | date= 8 August 2018 | issn= 0004-9425 | url= https://www.publish.csiro.au/ch/ch18283 |doi=10.1071/CH18283}}</ref> | |||

***''Melaleuca bracteata'' (only in certain chemotypes)<ref name="Brophy2013" /> | ***''Melaleuca bracteata'' (only in certain chemotypes)<ref name="Brophy2013" /> | ||

***''Melaleuca squamophloia'' | ***''Melaleuca squamophloia'' | ||

| Line 627: | Line 643: | ||

***''Cinnamomum tamala'' | ***''Cinnamomum tamala'' | ||

***''Cinnamomum wilsoni'' | ***''Cinnamomum wilsoni'' | ||

***''Lagarostrobos franklinii''<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Deans, B.J.)),((De Salas. J)), ((Smith, J.A)),((Bissember, A.C)) | journal= Australian Journal of Chemistry |title= Natural Products Isolated from Endemic Tasmanian | |||

Vascular Plants | volume= 71 | pages= 756-767 | date= 8 August 2018 | issn= 0004-9425 | url= https://www.publish.csiro.au/ch/ch18283 |doi=10.1071/CH18283}}</ref> | |||

***''Laurus nobilis'' (Bay tree) | ***''Laurus nobilis'' (Bay tree) | ||

***''Illicium anisatum'' | ***''Illicium anisatum'' | ||

| Line 831: | Line 849: | ||

***''Litoria'' Spp. | ***''Litoria'' Spp. | ||

***''Rana'' Spp. | ***''Rana'' Spp. | ||

*Bufotoxins | *[[List of bufotoxins|Bufotoxins]] | ||

**[[5-HO-DMT]] (bufotenin) | **[[5-HO-DMT]] (bufotenin) | ||

***Toads | ***Toads | ||

| Line 976: | Line 994: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

*[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallucinogenic_plants_in_Chinese_herbals Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals (Wikipedia)] | |||

*[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_psychoactive_plants,_fungi,_and_animals List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals (Wikipedia)] | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_psychoactive_plants,_fungi,_and_animals List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals (Wikipedia)] | ||

*[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_psychoactive_plants List of psychoactive plants (Wikipedia)] | *[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_psychoactive_plants List of psychoactive plants (Wikipedia)] | ||

| Line 999: | Line 1,018: | ||

[[Category:Substance-related lists]] | [[Category:Substance-related lists]] | ||

[[Category:Naturally-occurring substance|*]] | [[Category:Naturally-occurring substance|*]] | ||

{{#set:Featured=true}} | {{#set:Featured=true}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:08, 1 March 2025

Research safety before use While the following list of plants can be beneficial for various purposes, it's important to note that some of these organisms may contain toxic substances (especially those without articles) in addition, which may pose potential risks if ingested or handled improperly. Before incorporating any of these organisms into your home or garden, we strongly recommend conducting thorough research to understand the specific safety considerations and taking appropriate precautions, especially if you have children or pets. For more information see: Poisonous animals, fungus, and plants. And deadly fungus species. |

Naturally occurring sources refers to psychoactive chemicals or their precursors that already exist in nature. This is in contrast to synthetic psychoactive compounds which are artificially produced or designed in laboratories, psychoactive substances derived from artificial fungi biotransformation, or psychoactive substances, and precursor chemicals, produced by GMOs. However, these natural chemicals can often be reproduced synthetically as well, though notably they appear in nature or through human cultivation.

Proposed origins

There are a variety of proposed reasons for the appearance of psychoactive substances in organisms including the following examples:

Selective breeding

Selective breeding is a method used by cultivators to add or remove traits from successive generations of organisms by breeding together those that have the preferred properties in hopes of developing a desirable genetic strain. This may have resulted in both the potency and appearance of psychoactive substance(s) which the cultivators wished to produce.[1]

Defense mechanism

Another proposed reason for the presence of psychoactive substances in nature is their use as a defence mechanism. Through natural selection an organism may develop a poison or toxin useful for fending off predators,[2] as can be seen in Latrodectus Spiders who's psychoactive Latrotoxin has no reward value, and instead poses a threat to others.

Reward symbiosis

It is also possible that co-evolution encouraged psychoactive organisms to appear as a means of propagation. That is; in the same way sweet fruits were naturally selected by animals spreading their contained seeds, so were psychoactive flora that posed some benefit to the animals.[3]

Genetic similarity

An incidental cause of the prevalence of these substances is the shared genetic origins of the organisms. Given that they share a great deal of genetic code it is reasonable to assume that this may have been a factor in producing chemicals similar enough to neurotransmitters so as to activate receptor sites. For example many psychoactive chemicals are biosynthesized from amino acids such as tryptophan, while in humans this amino acid is used to make serotonin. The result is that some of the tryptamines in nature are serotonergic agonists when consumed.

Historical significance

The use of psychoactive substances is deeply rooted in human culture and dates back to pre-history. Early societies often incorporated these organisms into their traditions in medicine, spirituality, or recreation, such as the use of soma in the origins of Hinduism, and many of these uses continue into the modern day. Some common examples of this are the use of wine containing Ethanol in Christian communion, and Ayahuasca among indigenous peoples of the Amazon.

Many of these organisms have been instrumental to the progress of various scientific fields, such as Biology, Medicine, Psychonautics, and continue to reveal their importance with their involvement in major discoveries, such as the discovery of cannabinoid receptors[4] preceding our knowledge of endocannabinoids.[5]

Precluding endogenous chemicals, many of these organisms served as humanities only means of altering neurochemistry until the advent of synthetic psychoactives during the modern age. They have been at the forefront of major historical developments, such as pharmacotherapy, the funding of organized crime, the psychedelic era of the 60's, and the current "War on Drugs".

Examples

Below is an index of articles regarding natural sources of psychoactive substances. Other than inanimate sources they are categorized by kingdom of organism with sections for each applicable class of psychoactivity, sub-sections are given to active constituents, and finally the taxonomy and common name. Names may appear more than once if they contain a variety of substances, or their active substance has a variety of effects. Please note the quantity of substance obtained through an organism is not always safe and/or effective at common levels of consumption, but they are here included for sake of completeness. In addition some of the organisms are toxic or dangerous and thus proper research and preparation is recommended before attempting to personally investigate their activity.

Botanical sources

|

External links

References

|