Novel cognitive states

A novel cognitive state can be defined as any alteration of one's consciousness which does not merely amplify or suppress familiar states of mind, but rather induces an experience that is qualitatively different from that of ordinary consciousness.

This page lists and describes the various novel states which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Cognitive euphoria

Cognitive euphoria (semantically the opposite of cognitive dysphoria) is medically recognized as a cognitive and emotional state in which a person experiences intense feelings of well-being, elation, happiness, excitement, and joy.[1] Although euphoria is an effect (i.e. a substance is euphorigenic),[2][3] the term is also used colloquially to define a state of transcendent happiness combined with an intense sense of contentment.[4] However, recent psychological research suggests euphoria can largely contribute to but should not be equated with happiness.[5]

Cognitive euphoria is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as physical euphoria and tactile intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of opioids, entactogens, stimulants, and GABAergic depressants. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids.

Cognitive dysphoria

Cognitive dysphoria (semantically the opposite of euphoria) is medically recognized as a cognitive and emotional state in which a person experiences intense feelings of dissatisfaction, and in some cases indifference to the world around them.[6][7] These feelings can vary in their intensity depending on the dosage consumed and the user's susceptibility to mental instability. Although dysphoria is an effect, the term is also used colloquially to define a state of general melancholic unhappiness (such as that of mild depression)[8][9] often combined with an overwhelming sense of discomfort and malaise.[10]

Cognitive dysphoria is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety and depression.[6][7][11] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of deliriant compounds, such as DPH and datura. However, it can also occur during a stimulant's offset and during the withdrawal symptoms of almost any substance.

Conceptual thinking

Conceptual thinking is defined as an alteration to the nature and content of one's internal thought stream. This alteration predisposes a user to think thoughts which are no longer primarily comprised of words and linear sentence structures. Instead, thoughts become equally comprised of what is perceived to be incredibly detailed renditions of the innately understandable and internally stored concepts for which no words exist. Thoughts cease to be spoken by an internal narrator and are instead “felt” and intuitively understood.

For example, if a person was to think of an idea such as a "chair" during this state, one would not hear the word as part of an internal thought stream, but would feel the internally stored, pre-linguistic and innately understandable data which comprises the specific concept labelled within one's memory as a "chair". These conceptual thoughts are felt in a comprehensive level of detail that feels as if it is unparalleled within the primarily linguistic thought structure of everyday life. This is sometimes interpreted by those who undergo it as some "higher level of understanding".

During this experience, conceptual thinking can cause one to feel not just the entirety of a concept's attributed data, but also how a given concept relates to and depends upon other known concepts. This can result in the perception that the person can better comprehend the complex interplay between the idea that is being contemplated and how it relates to other ideas.

Conceptual thinking is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression and analysis enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Delusions

A delusion is a false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly held despite what almost everyone else believes and despite what constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the contrary. The belief is not ordinarily accepted by other members of the person's culture or subculture (i.e., it is not an article of religious faith). When a false belief involves a value judgement, it is regarded as a delusion only when the judgement is so extreme as to defy credibility. Delusional conviction can sometimes be inferred from an overvalued idea (in which case the individual has an unreasonable belief or idea but does not hold it as firmly as is the case with a delusion).[12][13][14]

This article focuses primarily on the types of delusion that are commonly induced by hallucinogens or other psychoactive substances, as opposed to the various categories that are listed within the DSM as occurring within people who suffer from psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Although there are common themes between these two causes of delusion, the underlying circumstances are distinct enough that they are seemingly very different in their themes, behaviour, and frequency of occurrence.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, delusions can usually be broken out of when overwhelming evidence is provided to the contrary or when the person has sobered up enough to logically analyse the situation. It is exceedingly rare for hallucinogen induced delusions to persist into sobriety.

It is also worth noting that delusions can often spread between individuals in group settings.[15] For example, if one person makes a verbal statement regarding a delusional belief they are currently holding while in the presence of other similarly intoxicated people, these other people may also begin to hold the same delusion. This can result in shared hallucinations and a general reinforcement of the level of conviction in which they are each holding the delusional belief.

Delusions are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, deliriants, and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, stimulant psychosis, and sleep deprivation. They are most likely to occur during states of memory suppression and share common themes and elements with clinical schizophrenia.

Depersonalization

Depersonalization or depersonalisation (sometimes abbreviated as DP) is medically recognized as the experience of feeling detached from, and as if one is an outside observer of, one's thoughts, body, or actions.[12][16][17][18] During this state, the affected person may feel like they are "on autopilot" and that the world is lacking in significance.[18][19] Individuals who experience depersonalization feel detached from aspects of the self, including feelings (e.g., "I know I have feelings but I don't feel them"),[20] thoughts (e.g., "My thoughts don't feel like my own")[21], and sensations (e.g., touch, hunger, thirst, libido).[17][22][23] This can be distressing to the user, who may become disoriented by the loss of a sense that their self is the origin of their thoughts and actions.

It is perfectly normal for people to slip into this state temporarily,[24] often without even realizing it. For example, many people often note that they enter a detached state of autopilot during stressful situations or when performing monotonous routine tasks such as driving.

It is worth noting that this state of mind is also commonly associated with and occurs alongside derealization. While depersonalization is the subjective experience of unreality in one's sense of self, derealization is the perception of unreality in the outside world.[16][17][19][22][23]

Depersonalization is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety,[17][20] depression,[20] time distortion,[21] and derealization.[22][25] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of dissociative compounds, such as ketamine,[24] PCP,[26][27] and DXM. However, it can also occur under the influence of cannabis,[24][25][28] psychedelics,[24] and to a lesser extent during the withdrawal symptoms of depressants[29][30] and SSRI's[24].

Depression

Depression medically encompasses a variety of different mood disorders whose common features are a sad, empty, or irritable mood accompanied by bodily and cognitive changes that significantly affect an individual's ability to function.[31][32] These different mood disorders have different durations, timing, or presumed origin. Differentiating normal sadness/grief from a depressive episode requires a careful and meticulous examination. For example, the death of a loved one may cause great suffering, but it does not typically produce a medically defined depressive episode.[31]

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, depressivity is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, irritability and dysphoria. It is most commonly induced through prolonged chronic stimulant or depressant use, during the withdrawal symptoms of almost any substance, or during the comedown/crash of a stimulant. It is associated specifically with higher alcohol consumption.[33] However, it is worth noting that substance-induced depressivity is often much shorter lasting than clinical depression, usually subsiding once the effects or withdrawal symptoms of a drug have ended.

If you suspect you are experiencing symptoms of depression, it is highly recommended to seek therapeutic medical attention and/or a support group. Additionally, you may want to read the depression reduction effect.

Depression as an effect has an unfortunate non-specific definition. There are several other relevant terms which should be taken into account when trying to understand this state of mind. These are listed and described.

Derealization

Derealization or derealisation (sometimes abbreviated as DR) is medically recognized as the experience of feeling detached from, and as if one is an outside observer of, one's surroundings.[12][16] This effect is characterized by the individual feeling as if they are in a fog, dream, bubble, or something watched through a screen,[34] like a film or video game.[22] These feelings instill the person with a sensation of alienation and distance from those around them.

Derealization can be distressing to the user, who may become disoriented by the loss of the innate sense that their external environment is genuinely real. The loss of the sense that the external world is real can make it feel inherently artificial and lifeless.[22]

This state of mind is commonly associated with and often coincides with depersonalization. While derealization is a perception of the unreality of the outside world, depersonalization is a subjective experience of unreality in one's sense of self.

Derealization is often accompanied by various perceptual distortions such as visual acuity suppression, visual acuity enhancement, and perspective distortions.[22] Other coinciding effects include auditory distortions and depersonalization.[34][22] This effect is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of dissociative compounds, such as ketamine, PCP, and DXM. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent during the withdrawal symptoms of stimulants and depressants.

Deja-Vu

Déjà Vu (or Deja Vu) is defined as as any sudden inappropriate impression of familiarity of a present experience with an undefined past.[35][36][37][38] Its two critical components are an intense feeling of familiarity, and a certainty that the current moment is novel.[39] This term is a common phrase from the French language which translates literally into “already seen”. It is a well-documented phenomenon that can commonly occur throughout both sober living and under the influence of hallucinogens.

Within the context of psychoactive substance usage, many compounds are commonly capable of inducing spontaneous and often prolonged states of mild to intense sensations of déjà vu. This can provide one with an overwhelming sense that they have “been here before”. The sensation is also often accompanied by a feeling of familiarity with the current location or setting, the current physical actions being performed, the situation as a whole, or the effects of the substance itself.

This effect is often triggered despite the fact that during the experience of it, the person can be rationally aware that the circumstances of the “previous” experience (when, where, and how the earlier experience occurred) are uncertain or believed to be impossible.

Déjà vu is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as olfactory hallucinations and derealization.[40] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[41] such as psychedelics,[42] cannabinoids,[43] and dissociatives.

Ego replacement

Ego replacement is defined as the sudden perception that one's sense of self and personality has been replaced with that of another person's, a fictional character's, an animal's, or an inanimate object's perspective. This can manifest in a number of ways which include but are not limited to feeling is one has literally become another human, animal, or alien consciousness. During this state, the person will be unlikely to realize that their personality has been temporarily swapped with another's and will usually not remember their previous life.

Ego replacement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as delusions, psychosis, and memory suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.

Enhancement and suppression cycles

Enhancement and suppression cycles is defined as an effect which results in two opposite states of mind that do not occur simultaneously but instead swap between each other at seemingly random intervals. These intervals are generally 10-30 minutes in length but can occasionally be considerably shorter.

The first of these two alternate states can be described as the experience of cognitive enhancements which feel is if they drastically improve the person's ability to think clearly. This includes analysis enhancement, thought organization, and creativity enhancement.

The second of these two alternate states can be described as the experience of a range of cognitive suppressions which feel as if they drastically inhibit the person's ability to think clearly. These typically include specific effects such as creativity suppression, language suppression, and analysis suppression.

Enhancement and suppression cycles are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic tryptamines, such as psilocybin, ayahuasca, and 4-AcO-DMT.

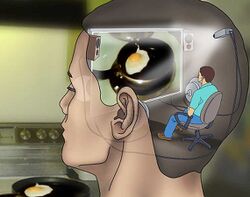

Perceived exposure to inner mechanics of consciousness

Perceived exposure to inner mechanics of consciousness can be described the experience of being exposed to an array of complex, autonomously-generated, cognitive sensations and conceptual thoughts which contain detailed sets of innately readable information.

The information within these sensations is felt to convey the organization, structure, architecture, framework and inner mechanics of the underlying programming behind all conscious and subconscious psychological processes. Those who undergo this effect commonly interpret the experience as suddenly having perceivable access to the inner workings of either the universe, reality, or consciousness itself.

The experience of this effect often feels capable of bestowing specific pieces of information onto trippers regarding the nature of human consciousness, and sometimes reality itself. The pieces of information felt to be revealed are highly varied, but some common sensations, revelations, and concepts are manifested between individuals. These generally include:

- Insight into the processes behind the direction, behavior, and content of one's conscious thought stream.

- Insight into the processes behind the organization, behavior, and content of one's short and long-term memory.

- Insight into the selection and behavior of one's responses to external input and decision-making processes as based on their individual personality.

- Insight into the origin and influences behind one’s character traits and beliefs.

These specific pieces of information are often felt and understood to be a profound unveiling of an undeniable truth at the time. Afterward, they are usually realized to be ineffable due to the limitations of human language and cognition, or simply nonsensical, and delusional due to the impairment caused by of other accompanying cognitive effects.

Perceived exposure to inner mechanics of consciousness is often accompanied by a vastly more complex and visual version of this effect which is referred to as Level 8B Geometry. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic tryptamines such as psilocin, ayahuasca, DMT, and 4-AcO-DMT. cannabinoids.

Feelings of impending doom

Feelings of impending doom are defined as the sudden sensations of overwhelming fear and urgency based on the belief that a negative event is about to occur in the immediate future. Negative events typically include some kind of medical emergency, such as the vasovagal response presenting as fainting during a blood donation;[44] fearing the potential to cause harm to others, being harmed, or dying;[45] or that the world is coming to an end. This effect can be the result of real evidence, but may also be based on an unfounded delusion or negative hallucinations. The intensity of these feelings can become overwhelming enough to trigger panic attacks.[46][47]

Feelings of impending doom are often accompanied by vague/paradoxical physical effects[44] and other coinciding effects such as anxiety, panic attacks,[48] and unspeakable horrors. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as deliriants like myristicin,[49][50][51][52] psychedelics,[53][54][55][56][57] and dissociatives. However, they can also occur during medical issues, cardiac arrest, mental illness, or interpersonal problems.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness can be described as a psychological concept which is well established within the scientific literature and commonly discussed in association with meditation.[58][59]

It is often broken down into two separate subcomponents which comprise this effect: The first of these components involves the self-regulation of attention so that its focus is completely directed towards immediate experience, thereby quietening one's internal narrative and allowing for increased recognition of external and mental events within the present moment.[60][61] The second of these components involves adopting a particular orientation toward one’s experiences in the present moment that is characterized by a lack of judgement, curiosity, openness, and acceptance.[62]

Within meditation, this state of mind is deliberately practised and maintained via the conscious and manual redirection of one's awareness towards a singular point of focus for extended periods of time. However, within the context of psychoactive substance usage, this state is often spontaneously induced without any conscious effort or the need of any prior knowledge regarding meditative techniques.

Mindfulness is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety suppression and focus intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids. However, it can also occur on entactogens, certain nootropics such as l-theanine, and during simultaneous doses of benzodiazepines and stimulants.

Paranoia

Paranoia is the suspiciousness or the belief that one is being harassed, persecuted, or unfairly treated.[63] These feelings can range from subtle and ignorable to intense and overwhelming enough to trigger panic attacks and feelings of impending doom. Paranoia also frequently leads to excessively secretive and overcautious behavior which stems from the perceived ideation of one or more scenarios, some of which commonly include: fear of surveillance, imprisonment, conspiracies, plots against an individual, betrayal, and being caught. This effect can be the result of real evidence, but is often based on assumption and false pretense.

Paranoia is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety and delusions. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as cannabinoids,[64] psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. However, it can also occur during the withdrawal symptoms of GABAergic depressants and during stimulant comedowns.

Personality regression

Personality regression is a mental state in which one suddenly adopts an identical or similar personality, thought structure, mannerisms and behaviours to that of their past self from a younger age.[65] During this state, the person will often believe that they are literally a child again and begin outwardly exhibiting behaviours which are consistent to this belief. These behaviours can include talking in a childlike manner, engaging in childish activities, and temporarily requiring another person to act as a caregiver or guardian. There are also anecdotal reports of people speaking in languages which they have not used for many years under the influence of this effect.[66]

Personality regression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, memory suppression, and ego dissolution. It is a relatively rare effect that is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, most notably Ayahuasca, LSD and Ibogaine in particular as well as certain dissociatives. However, it can also occur for people during times of stress,[65] as a response to childhood trauma, as a symptom of borderline personality disorder,[67] or as a regularly reoccuring facet of certain peoples lives that is not necessarily associated with any psychological problems.

Simultaneous emotions

Simultaneous emotions is defined as the experience of feeling multiple emotions simultaneously without an obvious external trigger. For example, during this state a user may suddenly feel intense conflicting emotions such as simultaneous happiness, sadness, love, hate, etc. This can result in states of mind in which the user can potentially feel any number of conflicting emotions in any possible combination.

Simultaneous emotions are often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression and emotion intensification. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Subconscious communication

Autonomous voice communication (also known as auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs))[68] is defined as the experience of being able to hear and converse with a disembodied and audible voice of unknown origin which seemingly resides within one's own head.[69][70][71][72] This voice is often capable of high levels of complex and detailed speech which are typically on par with the intelligence and vocabulary of ones own conversational abilities.

As a whole, the effect itself can be broken down into 5 distinct levels of progressive intensity, each of which are described below:

- A sensed presence of the other - The distinctive feeling that another form of consciousness is internally present alongside that of one's usual sense of self. This sensation is often referred to within the scientific literature as a "sense of presence".[70][73][74][75]

- Mutually generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are partially generated by one's own thought stream and in equal measure by that of a separate thought stream.[76]

- Separately generated internal responses - Internally felt conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which feel as if they are generated by an entirely distinct and separate thought stream that resides within one's head.[68][70][76]

- Separately generated audible internal responses - Internally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice within one's head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to one's own spoken voice.[69][76]

- Separately generated audible external responses - Externally heard conversational responses to one's own thoughts and feelings which are perceived as a clearly defined and audible voice which sounds as if it is coming from outside one's own head. These can take on a variety of voices, accents, and dialects, but usually sound identical to the person's own spoken voice.[69][70][76]

The speaker behind this voice is commonly interpreted by those who experience it to be the voice of their own subconscious, the psychoactive substance itself, a specific autonomous entity, or even supernatural concepts such as god, spirits, souls, and ancestors.

At higher levels, the conversational style of that which is discussed between both the voice and its host can be described as essentially identical in terms of its coherency and linguistic intelligibility as that of any other everyday interaction between the self and another human being of any age with which one might engage in conversation with. Higher levels may also manifest itself in multiple voices or even an ambiguous collection of voices such as a crowd.[70]

However, there are some subtle but identifiable differences between this experience and that of normal everyday conversations. These stem from the fact that one's specific set of knowledge, memories and experiences are identical to that of the voice which is being communicated with.[70][72] This results in conversations in which both participants often share an identical vocabulary down to the very use of their colloquial slang and subtle mannerisms. As a result of this, no matter how in-depth and detailed the discussion becomes, no entirely new information is ever exchanged between the two communicators. Instead, the discussion focuses primarily on building upon old ideas and discussing new opinions or perspectives regarding the previously established content of one's life.

Autonomous voice communication is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as delusions, autonomous entities, auditory hallucinations, and psychosis in a manner which can sometimes lead the person into believing the voices' statements unquestionably in a delusional manner. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. However, it may also occur during the offset of prolonged stimulant binges and less consistently under the influence of heavy dosages of cannabinoids.

Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation can be described as the experience of compulsive suicidal thoughts and a general desire to end one's own life. These thoughts patterns and desires range in intensity from fleeting thoughts to an intense fixation. This effect can also create a predisposition to other self-destructive behaviors such as self-harm or drug abuse and, if left unresolved, can eventually lead to attempts of suicide.

Suicidal ideation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as depression and motivation enhancement in a manner which maintains the person's negative view on life but also increases their will to take immediate action. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of various antidepressants of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor class. However, outside of psychoactive substance usage, it can also occur as a manifestation of a number of things including mental illness, traumatic life events, and interpersonal problems.

If you suspect that you are experiencing symptoms of suicidal ideation, it is highly recommended that you seek out therapy, medical attention, or a support group.

Thought loops

A thought loop is defined as the experience of becoming trapped within a chain of thoughts, actions and emotions which repeats itself over and over again in a cyclic loop. These loops usually range from anywhere between 5 seconds and 2 minutes in length. However, some users have reported them to be up to a few hours in length. It can be extremely disorientating to undergo this effect and it often triggers states of progressive anxiety within people who may be unfamiliar with the experience. The most effective way to end a cycle of thought loops is to simply sit down and try to let go.

This state of mind is most likely to occur during states of memory suppression in which there is a partial or complete failure of the person's short-term memory. This may suggest that thought loops are the result of cognitive processes becoming unable to sustain themselves for appropriate lengths of time due to a lapse in short-term memory, resulting in the thought process attempting to restart from the beginning only to fall short once again in a perpetual cycle.

Thought loops are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[77] such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of stimulants and benzodiazepines.

Time distortion

Time distortion is defined as an effect that makes the passage of time feel difficult to keep track of and wildly distorted.[78] It is usually felt in two different forms, time dilation and time compression.[79] These two forms are described and documented below:

Time dilation

Time dilation is defined as the feeling that time has slowed down.[80] This commonly occurs during intense hallucinogenic experiences and seems to stem from the fact that during an intense trip, abnormally large amounts of experience are felt in very short periods of time.[81][82] This can create the illusion that more time has passed than actually has. For example, at the end of certain experiences, one may feel that they have subjectively undergone days, weeks, months, years, or even infinite periods of time.

Time dilation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as spirituality intensification,[83] thought loops, novelty enhancement, and internal hallucinations in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately large number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[84][85] dissociatives, entactogens,[86][87] and cannabinoids.

Time compression

Time compression is defined as the experience of time speeding up and passing much quicker than it usually would while sober. For example, during this state a person may realize that an entire evening has passed them by in what feels like only a couple of hours.

This commonly occurs under the influence of certain stimulating compounds and seems to at least partially stem from the fact that during intense levels of stimulation, people typically become hyper-focused on activities and tasks in a manner which can allow time to pass them by without realizing it. However, the same experience can also occur on depressant compounds which induce amnesia. This occurs due to the way in which a person can literally forget everything that has happened while still experiencing the effects of the substance, thus giving the impression that they have suddenly jumped forward in time.

Time compression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression, focus intensification, stimulation, and amnesia in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately small number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of stimulating and/or amnesic compounds,[88] such as dissociatives,[89] entactogens, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines.

Time reversal

Time reversal is defined as the perception that the events, hallucinations, and experiences that occurred around one's self within the previous several minutes to several hours are spontaneously playing backwards in a manner which is somewhat similar to that of a rewinding VHS tape. During this reversal, the person's cognition and train of thought will typically continue to play forward in a coherent and linear manner while they watch the external environment around them and their body's physical actions play in reverse order. This can either occur in real time, with 5 minutes of time reversal taking approximately 5 minutes to fully rewind, or it can occur in a manner which is sped up, with 5 minutes of time reversal only taking less than a minute. It can reasonably be speculated that the experience of time reversal may potentially occur through a combination of internal hallucinations and errors in memory encoding.

Time reversal is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as internal hallucinations, thought loops, and deja vu. It is most commonly induced under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.

See also

References

- ↑ "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 821. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms.

- ↑ Drevets, Wayne C; Gautier, Clara; Price, Julie C; Kupfer, David J; Kinahan, Paul E; Grace, Anthony A; Price, Joseph L; Mathis, Chester A (2001). "Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria". Biological Psychiatry. 49 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01038-6. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ↑ Jônsson, Lars-Erik; Änggård, Erik; Gunne, Lars-M (1971). "Blockade of intravenous amphetamine euphoria in man". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 12 (6): 889–896. doi:10.1002/cpt1971126889. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ↑ Synofzik, Matthis; Schlaepfer, Thomas E.; Fins, Joseph J. (2012). "How Happy Is Too Happy? Euphoria, Neuroethics, and Deep Brain Stimulation of the Nucleus Accumbens". AJOB Neuroscience. 3 (1): 30–36. doi:10.1080/21507740.2011.635633. ISSN 2150-7740.

- ↑ Lucas, Richard E.; Diener, Ed; Suh, Eunkook (1996). "Discriminant validity of well-being measures". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 71 (3): 616–628. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.616. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 821. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Zoellner, Lori A.; Pruitt, Larry D.; Farach, Frank J.; Jun, Janie J. (2014). "UNDERSTANDING HETEROGENEITY IN PTSD: FEAR, DYSPHORIA, AND DISTRESS". Depression and Anxiety. 31 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1002/da.22133. ISSN 1091-4269.

- ↑ Epkins, Catherine C. (1996). "Cognitive specificity and affective confounding in social anxiety and dysphoria in children". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 18 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1007/BF02229104. ISSN 0882-2689.

- ↑ Bradley, Brendan P.; Mogg, Karin; Lee, Stacey C. (1997). "Attentional biases for negative information in induced and naturally occurring dysphoria". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 35 (10): 911–927. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00053-3. ISSN 0005-7967.

- ↑ Disner, Seth G.; Beevers, Christopher G.; Haigh, Emily A. P.; Beck, Aaron T. (2011). "Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (8): 467–477. doi:10.1038/nrn3027. ISSN 1471-003X.

- ↑ Koster, Ernst H. W.; De Raedt, Rudi; Goeleven, Ellen; Franck, Erik; Crombez, Geert (2005). "Mood-Congruent Attentional Bias in Dysphoria: Maintained Attention to and Impaired Disengagement From Negative Information". Emotion. 5 (4): 446–455. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.4.446. ISSN 1931-1516.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 819–20. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "DSM5Glossary" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Kiran, C., Chaudhury, S. (1 January 2009). "Understanding delusions". Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 18 (1): 3. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.57851. ISSN 0972-6748.

- ↑ Garety, P. A., Freeman, D. (June 1999). "Cognitive approaches to delusions: A critical review of theories and evidence". British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 38 (2): 113–154. doi:10.1348/014466599162700. ISSN 0144-6657.

- ↑ Arnone, D., Patel, A., Tan, G. M.-Y. (8 August 2006). "The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature". Annals of General Psychiatry. 5 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-5-11. ISSN 1744-859X.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Depersonalization-derealization disorder". International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Kolev, O. I., Georgieva-Zhostova, S. O., Berthoz, A. (28 January 2014). "Anxiety Changes Depersonalization and Derealization Symptoms in Vestibular Patients". Behavioural Neurology. 2014: e847054. doi:10.1155/2014/847054. ISSN 0953-4180.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sierra, M., Senior, C., Dalton, J., McDonough, M., Bond, A., Phillips, M. L., O’Dwyer, A. M., David, A. S. (1 September 2002). "Autonomic Response in Depersonalization Disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry. 59 (9): 833. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.833. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Radovic, F., Radovic, S. (2002). "Feelings of Unreality: A Conceptual and Phenomenological Analysis of the Language of Depersonalization". Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology. 9 (3): 271–279. doi:10.1353/ppp.2003.0048. ISSN 1086-3303.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Phillips, M. L., Medford, N., Senior, C., Bullmore, E. T., Suckling, J., Brammer, M. J., Andrew, C., Sierra, M., Williams, S. C. R., David, A. S. (December 2001). "Depersonalization disorder: thinking without feeling". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 108 (3): 145–160. doi:10.1016/S0925-4927(01)00119-6. ISSN 0925-4927.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Melges, F. T. (1 September 1970). "Temporal Disintegration and Depersonalization During Marihuana Intoxication". Archives of General Psychiatry. 23 (3): 204. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01750030012003. ISSN 0003-990X.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Dissociative Disorders. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) (Fifth Edition ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 22 May 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm08. ISBN 9780890425558.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Sierra, M., Baker, D., Medford, N., David, A. S. (October 2005). "Unpacking the depersonalization syndrome: an exploratory factor analysis on the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale". Psychological Medicine. 35 (10): 1523–1532. doi:10.1017/S0033291705005325. ISSN 0033-2917.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Stein, D. J., Simeon, D. (September 2009). "Cognitive-Affective Neuroscience of Depersonalization". CNS Spectrums. 14 (9): 467–471. doi:10.1017/S109285290002352X. ISSN 1092-8529.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Mathew, R. J., Wilson, W. H., Humphreys, D., Lowe, J. V., Weithe, K. E. (March 1993). "Depersonalization after marijuana smoking". Biological Psychiatry. 33 (6): 431–441. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(93)90171-9. ISSN 0006-3223.

- ↑ Erard, R., Luisada, P. V., Peele, R. (July 1980). "The PCP Psychosis: Prolonged Intoxication or Drug-Precipitated Functional Illness?". Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 12 (3–4): 235–251. doi:10.1080/02791072.1980.10471432. ISSN 0022-393X.

- ↑ Pradhan, S. N. (December 1984). "Phencyclidine (PCP): Some human studies". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 8 (4): 493–501. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(84)90006-X. ISSN 0149-7634.

- ↑ Mathew, R. J., Wilson, W. H., Chiu, N. Y., Turkington, T. G., Degrado, T. R., Coleman, R. E. (July 1999). "Regional cerebral blood flow and depersonalization after tetrahydrocannabinol adrninistration". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 100 (1): 67–75. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10916.x. ISSN 0001-690X.

- ↑ Roy-Byrne, P. P., Hommer, D. (June 1988). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal: Overview and implications for the treatment of anxiety". The American Journal of Medicine. 84 (6): 1041–1052. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(88)90309-9. ISSN 0002-9343.

- ↑ Duncan, J. (September 1988). "Neuropsychiatric aspects of sedative drug withdrawal". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 3 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1002/hup.470030304. ISSN 0885-6222.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Depressive Disorders". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm04.

- ↑ "Depressive Disorders". International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ↑ Conner, Kenneth R.; Pinquart, Martin; Gamble, Stephanie A. (2009). "Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 37 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007. ISSN 0740-5472.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Espiard, M.-L., Lecardeur, L., Abadie, P., Halbecq, I., Dollfus, S. (August 2005). "Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder after psilocybin consumption: a case study". European Psychiatry. 20 (5–6): 458–460. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.008. ISSN 0924-9338.

- ↑ O’Connor, A. R., Wells, C., Moulin, C. J. A. (9 August 2021). "Déjà vu and other dissociative states in memory". Memory. 29 (7): 835–842. doi:10.1080/09658211.2021.1911197. ISSN 0965-8211. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Funkhouser, A. T., Schredl, M. (2010). "The frequency of déjà vu (déjà rêve) and the effects of age, dream recall frequency and personality factors". doi:10.11588/IJODR.2010.1.473. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Brown, A. S. (2003). "A review of the déjà vu experience". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (3): 394–413. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.394. ISSN 1939-1455.

- ↑ Wild, E. (January 2005). "Deja vu in neurology". Journal of Neurology. 252 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s00415-005-0677-3. ISSN 0340-5354. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ O’Connor, A. R., Moulin, C. J. A. (June 2010). "Recognition Without Identification, Erroneous Familiarity, and Déjà Vu". Current Psychiatry Reports. 12 (3): 165–173. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0119-5. ISSN 1523-3812.

- ↑ Warren-Gash, C., Zeman, A. (1 February 2014). "Is there anything distinctive about epileptic deja vu?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 85 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-303520. ISSN 0022-3050. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Doss, M. K., Samaha, J., Barrett, F. S., Griffiths, R. R., Wit, H. de, Gallo, D. A., Koen, J. D. (2022), Unique Effects of Sedatives, Dissociatives, Psychedelics, Stimulants, and Cannabinoids on Episodic Memory: A Review and Reanalysis of Acute Drug Effects on Recollection, Familiarity, and Metamemory, Neuroscience, retrieved 16 June 2022

- ↑ Luke, D. P. (2008). "Psychedelic substances and paranormal phenomena: a review of the research". Journal of Parapsychology. 72: 77–107. ISSN 0022-3387. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ Basu, D., Malhotra, A., Bhagat, A., Varma, V. K. (1999). "Cannabis Psychosis and Acute Schizophrenia". European Addiction Research. 5 (2): 71–73. doi:10.1159/000018968. ISSN 1022-6877. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Gilchrist, P. T., Ditto, B. (January 2015). "Sense of impending doom: Inhibitory activity in waiting blood donors who subsequently experience vasovagal symptoms". Biological Psychology. 104: 28–34. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.11.006. ISSN 0301-0511. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ Poxon, L. H. (2013). ""Doing the same puzzle over and over again": a qualitative analysis of feeling stuck in grief". doi:10.15123/PUB.3490. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Kanner, A. M. (June 2004). "Recognition of the Various Expressions of Anxiety, Psychosis, and Aggression in Epilepsy". Epilepsia. 45 (s2): 22–27. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.452004.x. ISSN 0013-9580. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Hibbert, G. A. (28 January 1984). "Hyperventilation as a cause of panic attacks". BMJ. 288 (6413): 263–264. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6413.263. ISSN 0959-8138. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 826–7. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms.

- ↑ Abernethy, M. K., Becker, L. B. (September 1992). "Acute nutmeg intoxication". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (5): 429–430. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(92)90069-A. ISSN 0735-6757. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Demetriades, A. K., Wallman, P. D., McGuiness, A., Gavalas, M. C. (1 March 2005). "Low cost, high risk: accidental nutmeg intoxication". Emergency Medicine Journal. 22 (3): 223–225. doi:10.1136/emj.2002.004168. ISSN 1472-0205. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Milhorn, H. T. (2018). "Substance Use Disorders". Hallucinogen Dependence. Springer International Publishing. pp. 167–177. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-63040-3_12. ISBN 9783319630397.

- ↑ Alao, D., Guly, H. R. (1 March 2005). "Missed clavicular fracture; inadequate radiograph or occult fracture?". Emergency Medicine Journal. 22 (3): 232–233. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.013425. ISSN 1472-0205. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Di Cyan, E. (1971). "Poetry and Creativeness: With Notes on the Role of Psychedelic Agents". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 14 (4): 639–650. doi:10.1353/pbm.1971.0044. ISSN 1529-8795. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Obreshkova, D., Kandilarov, I., Angelova, V. T., Iliev, Y., Atanasov, P., Fotev, P. S. (January 2017). "PHARMACO - TOXICOLOGICAL ASPECTS AND ANALYSIS OF PHENYLALKYLAMINE AND INDOLYLALKYLAMINE HALLUCINOGENS (REVIEW)" (PDF). PHARMACIA. 64 (1).

- ↑ Geiger, H. A., Wurst, M. G., Daniels, R. N. (17 October 2018). "DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Psilocybin". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (10): 2438–2447. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00186. ISSN 1948-7193. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Kamińska, K., Świt, P., Malek, K. (21 January 2021). "2-(4-Iodo-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)- N -[(2-methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine (25I-NBOME): A Harmful Hallucinogen Review". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 44 (9): 947–956. doi:10.1093/jat/bkaa022. ISSN 0146-4760. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Cohen, S. (1 May 1963). "Prolonged Adverse Reactions to Lysergic Acid Diethylamide". Archives of General Psychiatry. 8 (5): 475. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1963.01720110051006. ISSN 0003-990X. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ Slagter, H. A., Davidson, R. J., Lutz, A. (2011). "Mental Training as a Tool in the Neuroscientific Study of Brain and Cognitive Plasticity". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 5. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00017. ISSN 1662-5161.

- ↑ Pagnini, F., Philips, D. (April 2015). "Being mindful about mindfulness". The Lancet Psychiatry. 2 (4): 288–289. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00041-3. ISSN 2215-0366.

- ↑ Baer, R. A. (2003). "Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 10 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. ISSN 1468-2850.

- ↑ Creswell, J. D. (3 January 2017). "Mindfulness Interventions". Annual Review of Psychology. 68 (1): 491–516. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. ISSN 0066-4308.

- ↑ Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., Devins, G. (2004). "Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 11 (3): 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077. ISSN 1468-2850.

- ↑ "Glossary of Technical Terms". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.): 826. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.GlossaryofTechnicalTerms.

- ↑ Freeman, D., Dunn, G., Murray, R. M., Evans, N., Lister, R., Antley, A., Slater, M., Godlewska, B., Cornish, R., Williams, J., Di Simplicio, M., Igoumenou, A., Brenneisen, R., Tunbridge, E. M., Harrison, P. J., Harmer, C. J., Cowen, P., Morrison, P. D. (March 2015). "How Cannabis Causes Paranoia: Using the Intravenous Administration of ∆ 9 -Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) to Identify Key Cognitive Mechanisms Leading to Paranoia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 41 (2): 391–399. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu098. ISSN 1745-1701.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Lokko, H. N., Stern, T. A. (14 May 2015). "Regression: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 17 (3): 27221. doi:10.4088/PCC.14f01761. ISSN 2155-7780.

- ↑ Fromm, E. (April 1970). "Age regression with unexpected reappearance of a repressed c3ildhood language". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 18 (2): 79–88. doi:10.1080/00207147008415906. ISSN 0020-7144.

- ↑ Viner, J. (January 1983). "An understanding and approach to regression in the borderline patient". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 24 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(83)90049-4. ISSN 0010-440X.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Toh, Wei Lin; Castle, David J.; Thomas, Neil; Badcock, Johanna C.; Rossell, Susan L. (2016). "Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) and related psychotic phenomena in mood disorders: analysis of the 2010 Survey of High Impact Psychosis (SHIP) data". Psychiatry Research. 243: 238–245. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.035. ISSN 0165-1781.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Moseley, Peter; Fernyhough, Charles; Ellison, Amanda (2013). "Auditory verbal hallucinations as atypical inner speech monitoring, and the potential of neurostimulation as a treatment option". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 37 (10): 2794–2805. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.10.001. ISSN 0149-7634.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 70.4 70.5 Woods, Angela; Jones, Nev; Alderson-Day, Ben; Callard, Felicity; Fernyhough, Charles (2015). "Experiences of hearing voices: analysis of a novel phenomenological survey". The Lancet Psychiatry. 2 (4): 323–331. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00006-1. ISSN 2215-0366.

- ↑ Romme, M. A. J.; Honig, A.; Noorthoorn, E. O.; Escher, A. D. M. A. C. (2018). "Coping with Hearing Voices: An Emancipatory Approach". British Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (01): 99–103. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.1.99. ISSN 0007-1250.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Corstens, Dirk; Longden, Eleanor; McCarthy-Jones, Simon; Waddingham, Rachel; Thomas, Neil (2014). "Emerging Perspectives From the Hearing Voices Movement: Implications for Research and Practice". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 40 (Suppl_4): S285–S294. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu007. ISSN 1745-1701.

- ↑ Fenelon, G.; Soulas, T.; de Langavant, L. C.; Trinkler, I.; Bachoud-Levi, A.-C. (2011). "Feeling of presence in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 82 (11): 1219–1224. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.234799. ISSN 0022-3050.

- ↑ Hayes, Jacqueline; Leudar, Ivan (2016). "Experiences of continued presence: On the practical consequences of 'hallucinations' in bereavement". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 89 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1111/papt.12067. ISSN 1476-0835.

- ↑ SherMer, M. (2010). The Sensed-Presence Effect. Scientific American, 302(4), 34. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-sensed-presence-effect/

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 Looijestijn, Jasper; Diederen, Kelly M.J.; Goekoop, Rutger; Sommer, Iris E.C.; Daalman, Kirstin; Kahn, René S.; Hoek, Hans W.; Blom, Jan Dirk (2013). "The auditory dorsal stream plays a crucial role in projecting hallucinated voices into external space". Schizophrenia Research. 146 (1-3): 314–319. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.004. ISSN 0920-9964.

- ↑ Bersani, Francesco Saverio; Corazza, Ornella; Albano, Gabriella; Valeriani, Giuseppe; Santacroce, Rita; Bolzan Mariotti Posocco, Flaminia; Cinosi, Eduardo; Simonato, Pierluigi; Martinotti, Giovanni; Bersani, Giuseppe; Schifano, Fabrizio (2014). "25C-NBOMe: Preliminary Data on Pharmacology, Psychoactive Effects, and Toxicity of a New Potent and Dangerous Hallucinogenic Drug". BioMed Research International. 2014: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2014/734749. ISSN 2314-6133.

- ↑ N. Stanciu, C., M. Penders, T. (1 June 2016). "Hallucinogen Persistent Perception Disorder Induced by New Psychoactive Substituted Phenethylamines; A Review with Illustrative Case". Current Psychiatry Reviews. 12 (2): 221–223.

- ↑ Nichols, D. E. (2016). "Psychedelics". Pharmacological Reviews. 68 (2): 264–355. doi:10.1124/pr.115.011478. ISSN 1521-0081.

- ↑ Pink-Hashkes, S., Rooij, I. J. E. I. van, Kwisthout, J. H. P. (2017). "Perception is in the details: A predictive coding account of the psychedelic phenomenon". London, UK : Cognitive Science Society.

- ↑ Hill, R. M.; Fischer, R.; Warshay, Diana (1969). "Effects of excitatory and tranquilizing drugs on visual perception. spatial distortion thresholds". Experientia. 25 (2): 171–172. doi:10.1007/BF01899105. ISSN 0014-4754.

- ↑ Fischer, R. (1971). "A Cartography of the Ecstatic and Meditative States". Science. 174 (4012): 897–904. doi:10.1126/science.174.4012.897. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Buckley, P. (1981). "Mystical Experience and Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 7 (3): 516–521. doi:10.1093/schbul/7.3.516. ISSN 0586-7614.

- ↑ Schroll, M. A. (2013). "From ecopsychology to transpersonal ecosophy: Shamanism, psychedelics and transpersonal psychology" (PDF). European Journal of Ecopsychology. 4: 116–144.

- ↑ Riley, Sarah C.E.; Blackman, Graham (2009). "Between Prohibitions: Patterns and Meanings of Magic Mushroom Use in the UK". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1080/10826080701772363. ISSN 1082-6084.

- ↑ Nikolova, I.; Danchev, N. (2014). "Piperazine Based Substances of Abuse: A new Party Pills on Bulgarian Drug Market". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 22 (2): 652–655. doi:10.1080/13102818.2008.10817529. ISSN 1310-2818.

- ↑ Yeap, C. W., Bian, C. K., Abdullah, A. F. L. (2010). "A Review on Benzylpiperazine and Trifluoromethylphenypiperazine: Origins, Effects, Prevalence and Legal Status". Health and the Environment Journal. 1 (2): 38–50.

- ↑ Griffith, John D.; Nutt, John G.; Jasinski, Donald R. (1975). "A comparison of fenfluramine and amphetamine in man". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 18 (5part1): 563–570. doi:10.1002/cpt1975185part1563. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ↑ Corazza, Ornella; Assi, Sulaf; Schifano, Fabrizio (2013). "From "Special K" to "Special M": The Evolution of the Recreational Use of Ketamine and Methoxetamine". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 19 (6): 454–460. doi:10.1111/cns.12063. ISSN 1755-5930.