Theacrine

| Theacrine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical Nomenclature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common names | Theacrine, Temurin, Temorine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Substitutive name | 1,3,7,9-Tetramethyluric acid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematic name | 1,3,7,9-Tetramethylpurine-2,6,8-trione | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class Membership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychoactive class | Stimulant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical class | Xanthine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Routes of Administration | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interactions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary sheet: Theacrine |

Theacrine, (Teacrine) is a small alkaloid molecule which can be seen as a structurally modified version of caffeine, since it appears to be synthesized from caffeine in some plants. It is a bitter, white crystalline xanthine alkaloid and a stimulant drug that increases activity in the brain and induces temporary improvements including enhanced alertness, wakefulness, and locomotion.

The mechanisms of theacrine parallel that of caffeine for the most part, and while it seems to have a stimulatory effect in research rodents it occurs at a higher dose (and the exact oral dose where it peaks with theacrine is not known).

Unlike many other psychoactive drugs, this substance is legal and unregulated in nearly all parts of the world. Beverages containing caffeine, such as coffee, tea, soft drinks, and energy drinks, enjoy great popularity. Caffeine is the most commonly used drug in the world, with 90% of adults in North America consuming it on a daily basis. Global consumption of caffeine has been estimated at 120,000 tonnes per year, making it the world's most popular psychoactive substance. This amounts to one serving of a caffeinated beverage for every person every day.[1]

Chemistry

Caffeine, or (1,3,7-Trimethylpurine-2,6-dione) is an synthetic alkaloid with a substituted xanthine core. Xanthine is a substituted purine, which contains two fused rings, a pyrimidine and imidazole. Pryimidine is a 6 membered ring with nitrogen constituents at R1 and R3; imidazole is a 5 membered ring with nitrogen substituents at R1 and R3 . Xanthine contains oxygen groups double-bonded to R2 and R6. Caffeine contains additional methyl substitutions at R1, R3, and R7 of its structure, bound to the open nitrogen groups of the xanthine skeleton. It is an achiral aromatic compound.

Pharmacology

Caffeine acts through several mechanisms, but its most important effect is to counteract a substance called adenosine that naturally circulates at high levels throughout the body, and especially in the nervous system. In the brain, adenosine plays a generally protective role, part of which is to reduce neural activity levels. The principal mode of action behind caffeine is as a nonselective antagonist of adenosine receptors. The caffeine molecule is structurally similar to adenosine, and is thus capable of binding to adenosine receptors on the surface of cells without activating them, thereby acting as a competitive inhibitor.[2]

Along side of this, caffeine also has profound effects on most of the other major neurotransmitters, including dopamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and, in high doses, on norepinephrine,[3] and to a small extent epinephrine, glutamate, and cortisol. At high doses, exceeding 500 milligrams, caffeine inhibits GABA neurotransmission. GABA reduction explains why caffeine increases anxiety, insomnia, rapid heart and respiration rate at high dosages.

Metabolites

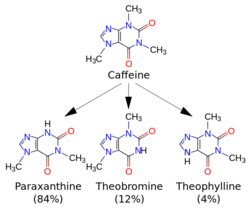

Caffeine is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 oxidase enzyme system, in particular, by the CYP1A2 isozyme, into three dimethylxanthines,[4] each of which has its own effects on the body:

- Paraxanthine (84%): Increases lipolysis, leading to elevated glycerol and free fatty acid levels in the blood plasma.

- Theobromine (12%): Dilates blood vessels and increases urine volume. Theobromine is also the principal alkaloid in the cocoa bean, and therefore chocolate.

- Theophylline (4%): Relaxes smooth muscles of the bronchi, and is used to treat asthma. The therapeutic dose of theophylline, however, is many times greater than the levels attained from caffeine metabolism.

Subjective effects

The effects listed below are based upon the subjective effects index and personal experiences of PsychonautWiki contributors. The listed effects will rarely (if ever) occur all at once, but heavier dosages will increase the chances and are more likely to induce a full range of effects.

Physical effects

- Stimulation - In terms of its effects on the physical energy levels of the user, caffeine is usually considered to be mildly to moderately energetic and stimulating in a fashion that is considerably weaker in comparison to that of traditional recreational stimulants such as amphetamine, MDMA or cocaine. This encourages physical activities such as performing chores and repetitive tasks which would otherwise be boring and strenuous physical activities. The particular style of stimulation which caffeine presents can be described as forced. This means that at higher dosages, it becomes difficult or impossible to keep still as jaw clenching, involuntarily bodily shakes and vibrations become present, resulting in extreme shaking of the entire body, unsteadiness of the hands, and a general lack of motor control.

- Frequent urination - When doses of caffeine equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee are administered to people who have not consumed caffeine during prior days, they produce a mild increase in urinary output.[5] Most people who consume caffeine, however, ingest it daily. Regular users of caffeine have been shown to develop a strong tolerance to the diuretic effect.[6]

- Vasoconstriction and Vasodilation - Whilst caffeine acts as a mild vasoconstrictor, its metabolite theobromine is a vasodilator and these effects are thought to cancel each other out.

- Bronchodilation - Caffeine is an effective bronchodilator. In clinical tests on adults with athsma, at fairly low doses (5mg/kg of body weight), caffeine has been shown to provide a small improvement in lung function, such that it needs to be controlled for in diagnostic tests.[7]

- Appetite suppression

- Dizziness

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Nausea - This mostly occurs at high doses.

- Tactile enhancement

- Bruxism - This effect does not occur as consistently as it does on other stimulants such as MDMA.

- Stamina enhancement

Cognitive effects

The cognitive effects of caffeine can be broken down into several components which progressively intensify proportional to dosage. It contains a large number of typical stimulant cognitive effects. Although negative side effects are usually mild at low to moderate dosages, they become increasingly likely to manifest themselves with higher amounts or extended usage. This particularly holds true during the offset of the experience.

The most prominent of these cognitive effects generally include:

- Analysis enhancement

- Anxiety

- Cognitive fatigue - This component can occur during the offset of this compound as a rebound effect which is usually equal in its intensity to the enhancements which occurred before it.

- Compulsive redosing - This effect is less persistent than it is with nicotine or cocaine.

- Euphoria - This effect is generally mild.

- Increased music appreciation

- Focus enhancement - This component is most effective at low to moderate dosages as anything higher will usually impair concentration.

- Increased libido

- Memory enhancement

- Motivation enhancement

- Thought acceleration

- Wakefulness

After effects

The effects which occur during the offset of a stimulant experience generally feel negative and uncomfortable in comparison to the effects which occurred during its peak. This is often referred to as a "comedown" and occurs because of neurotransmitter depletion. Its effects commonly include:

- Anxiety

- Cognitive fatigue

- Depression

- Irritability

- Motivation suppression

- Thought deceleration

- Wakefulness

Toxicity and harm potential

Caffeine is not known to cause brain damage, and has an extremely low toxicity relative to dose. There are relatively few physical side effects associated with caffeine exposure. Various studies have shown that in reasonable doses in a careful context, it presents no negative cognitive, psychiatric or toxic physical consequences of any sort.

Lethal dosage

Extreme overdose can result in death.[8][9] The median lethal dose (LD50) given orally is 192 milligrams per kilogram in rats. The LD50 of caffeine in humans is dependent on individual sensitivity, but is estimated to be about 150 to 200 milligrams per kilogram of body mass or roughly 80 to 100 cups of coffee for an average adult.[10] Though achieving lethal dose of caffeine would be difficult with regular coffee, it is easier to reach high doses with caffeine pills, and the lethal dose can be lower in individuals whose ability to metabolize caffeine is impaired.

It is strongly recommended that one use harm reduction practices when using this drug.

Tolerance and addiction potential

As with other stimulants, the chronic use of caffeine can be considered moderately addictive with a high potential for abuse and is capable of causing psychological dependence among certain users. When addiction has developed, cravings and withdrawal effects may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage.

Tolerance to many of the effects of caffeine develops with prolonged and repeated use. This results in users having to administer increasingly large doses to achieve the same effects. After that, it takes about 3 - 7 days for the tolerance to be reduced to half and 1 - 2 weeks to be back at baseline (in the absence of further consumption).

Some coffee drinkers develop tolerance to its sleep-disrupting effects, but others apparently do not.[11] Caffeine does not present a cross-tolerance with other common stimulants.

Withdrawal symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms -– including headaches, irritability, inability to concentrate, drowsiness, insomnia, and pain in the stomach, upper body, and joints –- may appear within 12 to 24 hours after discontinuation of caffeine intake, peak at roughly 48 hours, and usually last from 2 to 9 days.[12]Withdrawal headaches are experienced by 52% of people who stopped consuming caffeine for two days after an average of 235 mg caffeine per day prior to that.[13] In prolonged caffeine drinkers, symptoms such as increased depression and anxiety, nausea, vomiting, physical pains and intense desire for caffeine containing beverages are also reported. Peer knowledge, support and interaction may aid withdrawal.

Psychosis

There is limited evidence that caffeine, in high doses or when chronically abused, may induce psychosis in normal individuals and worsen pre-existing psychosis in those diagnosed with schizophrenia.[14][15] Caffeine has been shown to potentiate the effects of methamphetamine, which can also induce psychosis.[16][17]

Legal issues

|

This legality section is a stub. As such, it may contain incomplete or wrong information. You can help by expanding it. |

Caffeine is legal in nearly all parts of the world. Because caffeine is a psychoactive drug however, it is often regulated. For example, in the United States the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) restricts beverages to contain less than 0.02% caffeine [18] unless they are listed as a dietary supplement.[19]

See also

External links

- Caffeine (Wikipedia)

- Caffeine (Erowid)

- Caffeine experiences (Erowid)

- Caffeine (TripSit)

- Caffeine (The Drug Classroom)

References

- ↑ What's your poison? Caffeine | http://www.abc.net.au/quantum/poison/caffeine/caffeine.htm

- ↑ Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: mechanism of action | http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00018-003-3269-3

- ↑ http://worldofcaffeine.com/caffeine-and-neurotransmitters/

- ↑ The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base | https://www.pharmgkb.org/drug/PA448710#biotransformation

- ↑ Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x/abstract

- ↑ Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x/abstract

- ↑ Caffeine for asthma | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2/abstract

- ↑ Caffeine fatalities—four case reports | http://www.fsijournal.org/article/S0379-0738(03)00417-1/abstract

- ↑ Alstott RL, Miller AJ, Forney RB (1973). "Report of a human fatality due to caffeine". Journal of Forensic Science 18 (35).

- ↑ Factors Affecting Caffeine Toxicity: A Review of the Literature | http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.1552-4604.1967.tb00034.x/abstract

- ↑ Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use (PubMed.gov / NCBI) | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10049999

- ↑ A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features | http://webcitation.org/6533BsxXt

- ↑ Withdrawal Syndrome after the Double-Blind Cessation of Caffeine Consumption | http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199210153271601

- ↑ Caffeine-induced psychosis | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19407709

- ↑ Psychosis Following Excessive Ingestion of Energy Drinks in a Patient With Schizophrenia | http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09101456

- ↑ Caffeine enhances the stimulant effect of methamphetamine | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7862940

- ↑ Interaction between caffeine and methamphetamine by means of ambulatory activity in mice. | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2816095

- ↑ CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 | http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=182.1180&SearchTerm=caffeine

- ↑ Consumer Q&A: Caffeine-Containing Dietary Supplements | http://crnusa.org/caffeine/Q+A.html